Mike Oldfield’s third album, 1975’s Ommadawn, was recorded in the wake of his mother’s death. He was, in his own words, “barely communicating with my father”, and was struggling with

the stresses – manifesting as panic attacks – induced by the colossal success of his 1973 debut album Tubular Bells.

Forty years on, and latest work Return To Ommadawn was made in similarly turbulent circumstances. He had barely recovered from the all-time career high that was performing at the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony in London when his father passed away. And then, in 2015, his 33-year-old son Dougal suddenly died. “Sometimes life gives you these trials,” he told this writer recently. “The last four years have been very difficult.” Fortunately, he had somewhere to put all his emotions: his music. “Especially the guitar playing,” he said. “It sort of gives you power. Otherwise you make bland music that doesn’t really pull at the heart-strings.”

Here is where we finally lay to rest the idea of Oldfield as purveyor of innocuous so-called new age ambient snooze-ak. Better to file his music under “quietly intense”. Yes, there are gently plucked acoustic guitars and an air of serene contemplation. But beneath the seemingly tranquil surface the musician is peddling hard, trying to control the raging tumult within.

This new version of Ommadawn, then, finds Oldfield returning to a “musical state of mind”, to a place that allows him to feel centred and calm. But is it a step-by-step recreation of, or simply a nod to, the original? The credits include some of the same instruments for this, his first acoustic, stringed instrument-based album for

a while, such as the bodhrán and mandolin (which he rebuilt from the ones played on Ommadawn), and there is glockenspiel, although instead of the recorder he uses a penny whistle. Elsewhere, Oldfield handles electric guitar duties – a Gibson SG, as per the original – as well as acoustic bass, ukulele, African drums, and Celtic harp. Many of the keyboards were created using “virtual-reality” versions – plug-ins – for simplicity’s sake. This is a solo exercise,

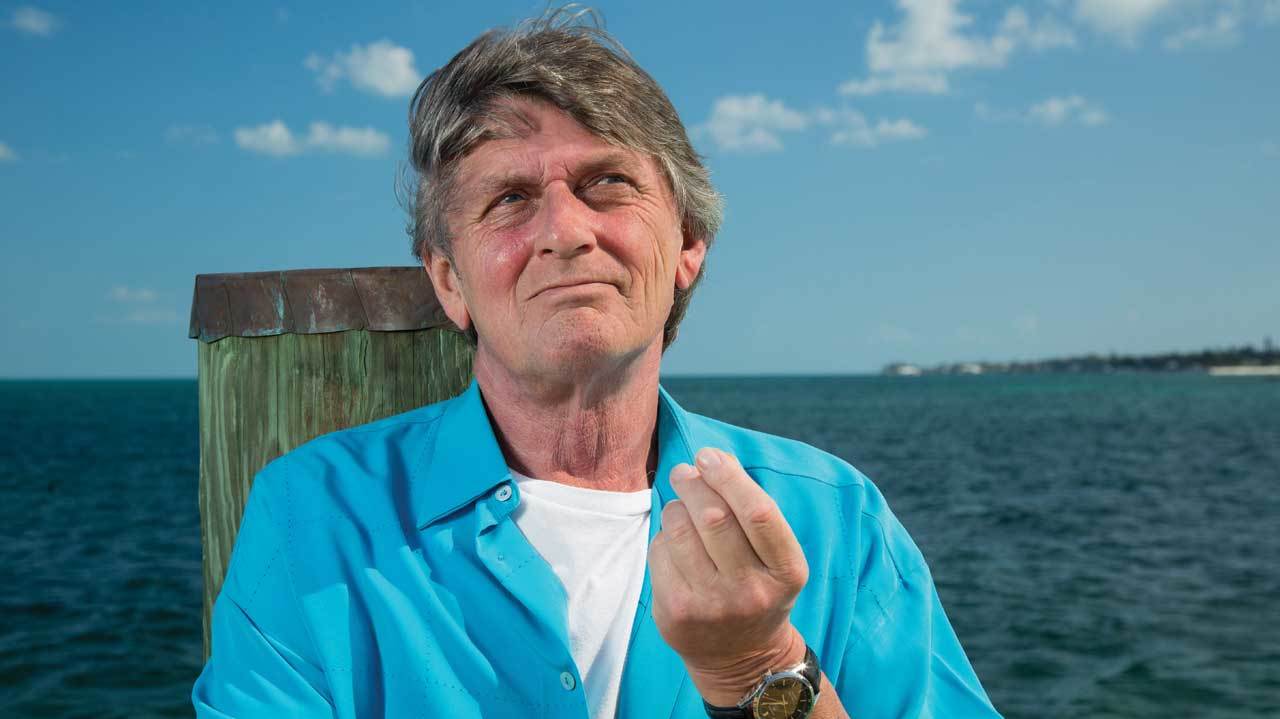

not peppered with cameo appearances like Ommadawn Mk 1: Oldfield lives an isolated existence these days in the Bahamas and the likes of Paddy Moloney and Bridget St John couldn’t just pop by, as they did when he was at the Beacon in Herefordshire.

There are pros and cons to this approach. On the one hand, Return To Ommadawn is Oldfield the solipsist wunderkind in excelsis, there is a consistency to the sound, and the fact that Oldfield did virtually everything adds to the feeling of a lovingly handcrafted piece of work. On the other, the original was more quixotic, with more twists and turns and a greater melodic and textural variety.

- Mike Oldfield on Tubular Bells, punk rock, and why you should get a lawyer

- What Mike Oldfield producer Tom Newman really thinks about Rob Reed's Sanctuary

- Mike Oldfield Quiz

- Why Mike Oldfield's returning to Ommadawn

Closer scrutiny reveals the occasional melodic fragment from the first Ommadawn, albeit in transposed form: “I thought there should be a few little things of the original album in there so I took some vocal bits, cut them in pieces, treated them, reversed them and edited them back together, and gradually over an afternoon a new melody appeared with a strange otherworldly sound,” Oldfield explained. Really, though, it’s a matter of overall atmosphere: this feels like Ommadawn revisited, and that’s paramount. It is broken up into Parts 1 and 2, each a little longer than on the original, and there is an echo of On Horseback towards the end of the latter. There are hours of fun to be had in playing “compare and contrast”. There is, for example, a similar plucked-guitar motif at around the 2:20 mark on both iterations of the album. There are rhythms that are distinctly tribal, reflecting the pioneering world music forays of version 1.0. Return To Ommadawn is a treat for fans of Oldfield the guitarist as he overdubs himself variously on acoustic flurries and plangent electric runs. It may not be as diverse as its forebear, more uniform, but it’s just as stirring, with all manner of cinematic theme music potential. There might not be anything here to suit

a movie, say, about a young female possessed by the devil, but certainly the opportunities to accompany rousing scenes of natural beauty are limitless.

But don’t be fooled by the aural splendour. There’s blood on these tracks.