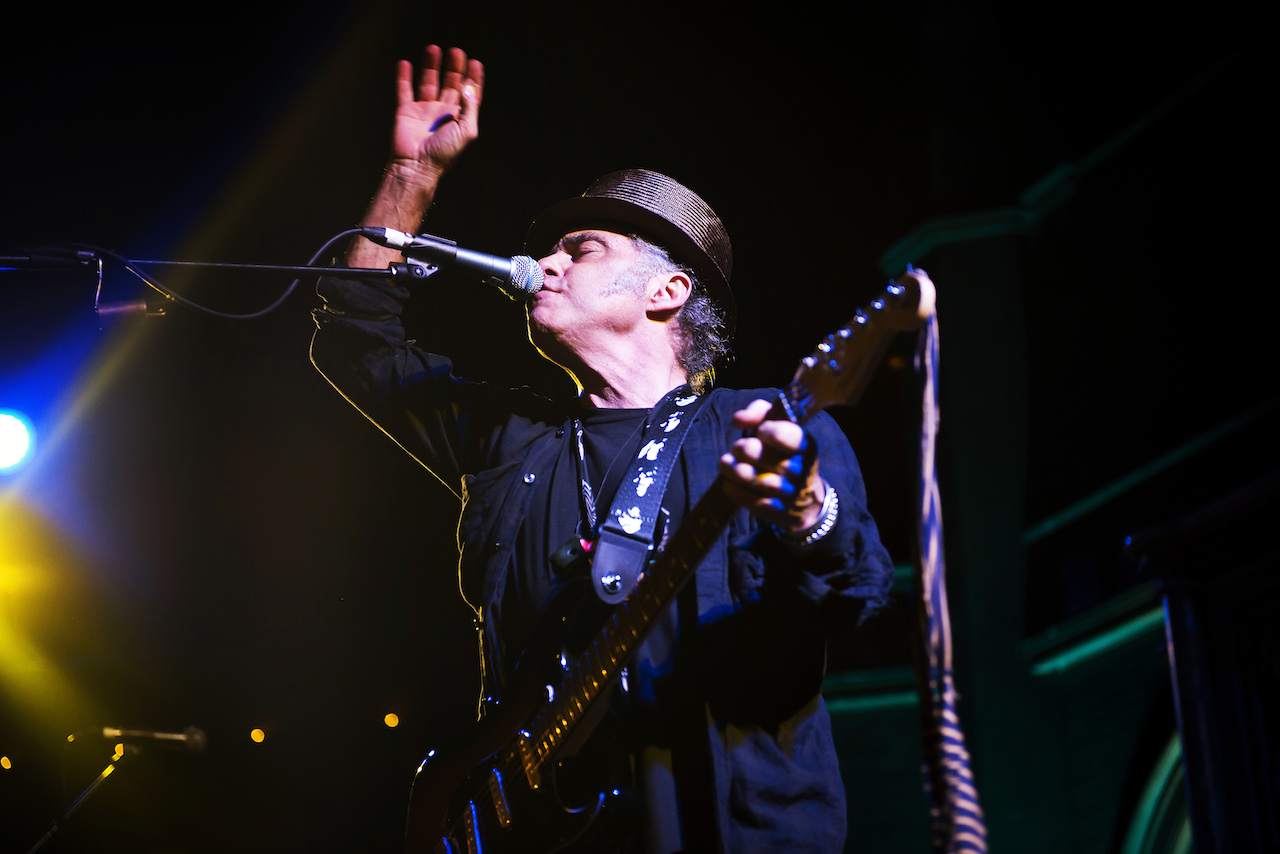

Looking half-street-punk, half-‘70s tramp in his battered top hat and waistcoat, Nils Lofgren may be the perennial sidekick, most famous for performing in the giant shadows of Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen, but he’s a more than adept frontman. On his first UK tour for several years, he’s the consummate entertainer, singing and playing guitar and occasional piano, aided and abetted by fellow keyboardist and guitarist Greg Varlotta, regaling us with anecdotes from his 46 years in the game, even tap-dancing. The latter isn’t just unexpected - it’s impressive from someone who, in 2008, had to have hip replacement surgery from years of playing basketball and back-flipping.

The latter is one thing we don’t get: the acrobatics on a trampoline that were, for years, part and parcel of a Lofgren show. Instead, we get vocal contortions as his gruffly boyish voice runs up and down the register, and guitar pyrotechnics as he uses a loop station and assorted pedals to effectively jam with himself, soloing on top of rhythms created on the fly.

The Chicago-born musician has quite a catalogue on which to draw, as last year’s Face The Music box set - comprising 10 CDs and 169 tracks - amply demonstrates. He delves back to his days with the band that he formed when he was 17, Grin, and the lovely Lost A Number. A winsomely pretty tune with a dose of grit from 1972’s superb 1+1 album (with its “rockin’” and “dreamy” sides) telling a sad tale about romantic disillusion and hard-won wisdom, it encapsulates many of the qualities that have made Lofgren so engaging over the last five decades. There follows a heart-warming story about being rescued as a teenager for a night from the New York streets by a merciful Sly Stone, and winding up sharing a hotel room with 30 stoned hippies. His Man In The Moon - “about kids in school going through it” - is similarly empathetic. It’s also an opportunity for some nimble finger-work, eliciting rapture from the crowd. He plays Black Books, his song that featured in The Sopranos, complete with rousing churchy synth chords, and puts on shades to get in the extra dark mood.

Lofgren has always been quick to acknowledge his heroes - an electrifying version of Keith Don’t Go, his ode to the Glimmer Twin, underlines that - but his bittersweet ballads and tender rockers have earned him a place of his own in the pantheon. He’s like a Springsteen without the bluster, a self-deprecating Bruce with a knack of writing his own epitaphs: Shines Silently becomes an audience singalong, and The Sun Hasn’t Set (On This Boy Yet) is a poignant reminder that he was once a serious contender. And then Varlotta starts tap-dancing and Lofgren puts on his special shoes and joins him for a synchronised routine, cartilage or no cartilage. He comes to dance. Literally.