One of the more fascinating aspects of prog’s second coming has been the emergence of bands who defy any easy pigeonholing.

Take North Atlantic Oscillation. The name may well be very prog-friendly – being both a bit of a mouthful and also a genuine phenomenon for climate nerds to get excited about – but their music is a little less definable, and much more thrilling.

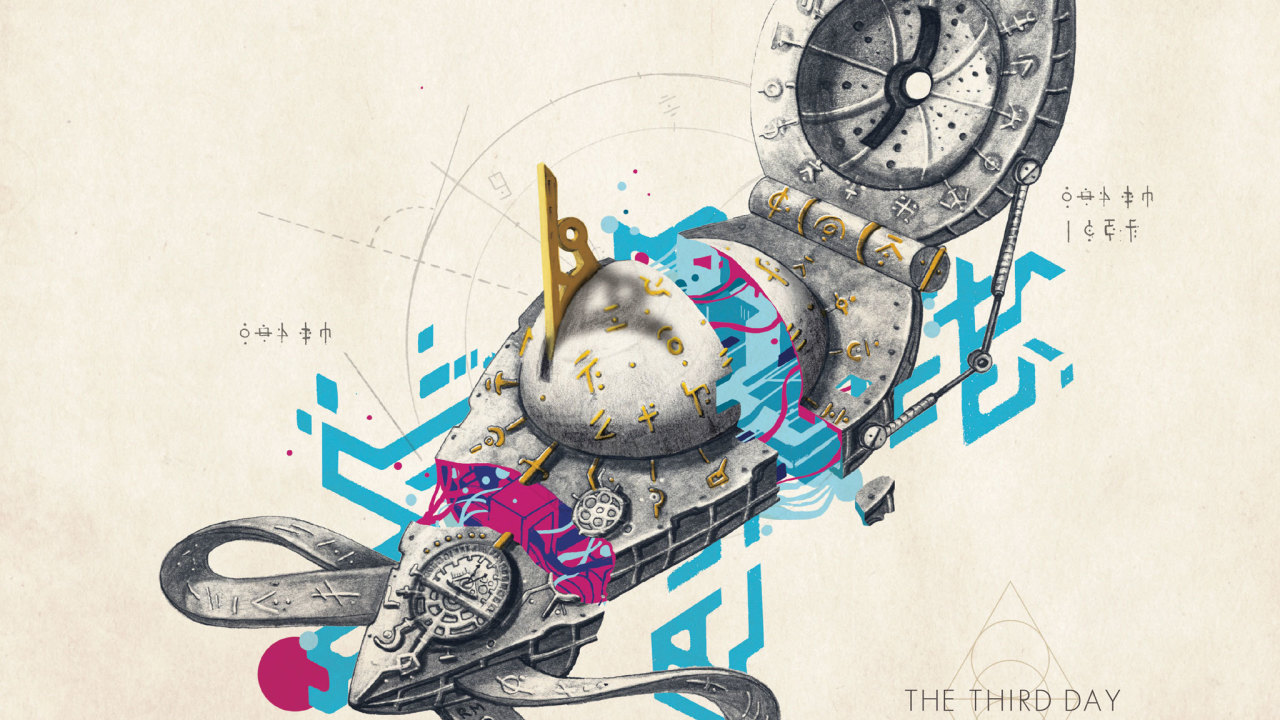

Grappling Hooks, the Edinburgh trio’s 2010 debut, suggested they were moody types in the tradition of Pink Floyd, peppered with the glitchy sensibility of Radiohead or Squarepusher. By 2012’s Fog Electric the band had grown into something more opulent, pushing their sound outwards with an intricate lacework of strings and synths. If anything, The Third Day signals a bolder statement of intent. This is big, bright, decidedly lush music with an almost operatic sense

of scope and design. It’s also frequently very beautiful.

NAO leader Sam Healy prides himself on being a stickler for fine detail, in particular the kinship between certain sympathetic sounds. Most of the guitars and vocals were cut in his home studio, where he constructed layers of noise on to which he could later add keyboards, abetted by Ben Martin (programming) and Chris Howard (bass, bass synth).

One of the album’s defining features is Martin’s hefty drum sound. Unlike the rest of the music, the beats were recorded in the rafters of an old Victorian mill. This might all sound like technical trivia, but it’s actually the key to a good deal

of The Third Day’s appeal. It’s this contrast between percussion and synthetic stylings that helps give the album a radiant, very human ambience.

The other factor is Healy’s keening voice. He’s a man with a lovely set of tonsils. And while it may be too early to plonk him in the same heightened company as Peter Gabriel or Guy Garvey, he’s certainly pointed that way. The comparisons don’t stop there. Like Elbow or solo Gabriel, NAO are clearly fans of great pop. The jubilant Great Plains II and Penrose feel like the kind of deceptively tricky confections that XTC started making in the early 90s. And while they also share a love of experimental music (see the ever so pastoral Wires), there’s an inherent accessibility to these moments that ensure they never disappear up their own rear.

For a ready illustration of what NAO do best, head for the final two tracks. Dust and When To Stop are both so perfectly weighted – sweeping delicate acoustics into a glorious panorama – that you really wish they’d go on forever. Progtronica at its very best.