You can trust Louder

Like the Lifetime Achievement Award, the full-on career retrospective is a mixed achievement for any artist. On the one hand, it’s an acknowledgement of a lasting career full of excellence and cultural import, taking in every aspect of the musician’s work from the pop hits to the rarities. On the other hand it’s an obituary, the entertainment world’s equivalent of the gold watch you used to get when you retired from the bank. This is the reason that acts as respected and enduring as AC/DC and The Rolling Stones resisted such tributes for as long as was possible, preferring to emphasise new material over oldies. The latter can be annoying: it’s great that these bands are still continuing to work but we would rather not wait until they’re no longer with us to enjoy their archives.

Focusing on his continuing profession has almost certainly been uppermost in Paul McCartney’s rationale. With even The Beatles’ catalogue recycled (and remixed) rather than milked for its obscurities, it was always unlikely that McCartney himself would mine the wealth of his own solo career for sessions, demos, B-sides, unreleased material and live shows, let alone bring out a massive Bob Dylan-style collection of official bootlegs. The odd extra track on a reissue aside, McCartney’s catalogue has always been treated, rightly, as the back pages of a still-working talent rather than a shopping trip down memory lane.

Some fans may want more. With a solo career that’s lasted 46 years (far exceeding the time he spent in The Beatles), Paul McCartney is someone who’s well worth a proper career retrospective (the 2001 Wingspan set was good, but only half the story). Pure McCartney isn’t quite that. Coming in three different formats – two CDs or four LPs or four CDs – the songs have been chosen by McCartney and “team” to provide a fun listening experience rather than a comprehensive and entirely representative look back at a reputation that grows with each passing year. As such, it avoids the Dylan approach of using out-takes and demos, is arranged by mood rather than chronology, and represents Macca’s work by bulk rather than selection. But then, this is the world’s greatest pop star, not a dusty bluesman (and while there’s none of his orchestral work, many fans will be pleased by the inclusion of some of his work with Youth as The Fireman).

So what does it look like, this massed McCartney? Is it, as his 70s critics would have it, a monstrous thump of sentiment and saccharine? Is it a ragingly optimistic tribute to thumbs and their elevation? Or is it an attempt to rewrite the history books and present Paul as a rocker, an avant-garde artist and/or Best One In The Beatles? Well, thanks to its aforementioned jumble of fun approach, the answer is, thankfully, none of these. The songs presented here are united only by their sheer McCartney-ness. Stadium opener Venus And Mars/Rock Show may be followed by the synth jitter of Temporary Secretary, the robust 2013 clatter of Queenie Eye may lead into kiddie mini opera We All Stand Together, and the casual sway of My Valentine might follow the Jacko duet Say Say Say, but everything here – ballads, stompers, floor fillers, whimsy, mimsy and out-and-out jaw-dropping ‘How does he do that?’ brilliance – has Paul McCartney running through it like the words ‘Channel Tunnel’ through a stick of rock that is itself running through the Channel Tunnel.

This might sound obvious, but think on: how many other artists have maintained a career of this length and variety and not veered into creative cul de sacs, badly advised midstream horse changes or just entire decades of dismalness? Even David Bowie, one of the few artists to combine genius, invention and commerce to an arguably equal degree, had to form Tin Machine – the anti Wings – to shake himself out of a nightmare pop career gone bad. But Paul McCartney – even when he’s making records that the cool kids hate – has always been effortlessly himself. You don’t have to love Mull Of Kintyre (but you should) to notice the casual confidence with which he delivers it; he knows it’s great, and he knows you’ll work it out one day.

He records Live And Let Die, a song which is both a day at the races and a night at the opera. He writes Jet, a woozy tribute to glam-era Bowie, and on the same album records Let Me Roll It, which may not be a dig at John Lennon but is one of the best Lennon records ever made. And he makes pop; so much pop that on occasion he finds himself compelled to defend it (Silly Love Songs asks and answers the question, ‘What’s wrong with that/I’d like to know’ before conceding helplessly, ‘And here I go/Again!’ It’s wonderful).

Where other long-haul artists (the Stones, Rod Stewart, the comparatively short-lived Led Zeppelin) either ploughed a stubbornly unvaried furrow or tried on different styles in an attempt to make being themselves less boring), McCartney has never gone disco or funked things up for the sake of it. He experiments because it’s fun or because it’s a fresh way to get ideas out (even 2013’s New with hip young chart producer Mark Ronson and 2005’s Chaos And Creation In The Backyard with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich sound more like vehicles for expressing Macca’s ideas than producer-led chart hounds). It doesn’t always work (2001’s Driving Rain is arid at times while 1986’s Press To Play sees some great songs produced into airlessness) but generally it does (The Fireman’s Electric Arguments). You could drop into this collection at any chronological point – 1981 or 1978 or 1998 or 2014 – and know immediately you were listening to a Paul McCartney record.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

One theme in particular recurs: hope in adversity. From Chaos And Creation…’s beautiful Too Much Rain, London Town’s With A Little Luck and the recent video game-inspired Hope For The Future, the idea than you may get knocked down but you will get up again is a classic McCartney notion which goes a long way to explaining why he will always be more popular than, say, Marilyn Manson or Radiohead.

There are songs here you may never have heard, or passed by on an album. There are songs which were covered by Guns N’ Roses, Rod Stewart and Michael Jackson. There are songs you may well loathe and songs you secretly love. And there are omissions, which is inevitable in a career that’s lasted longer than some countries. I would have liked Ever Present Past from Memory Almost Full, or something from the unreleased 1979 Wings show in Glasgow, or the horrifically underrated Mary Had A Little Lamb (just a beautiful melody) but, you know…

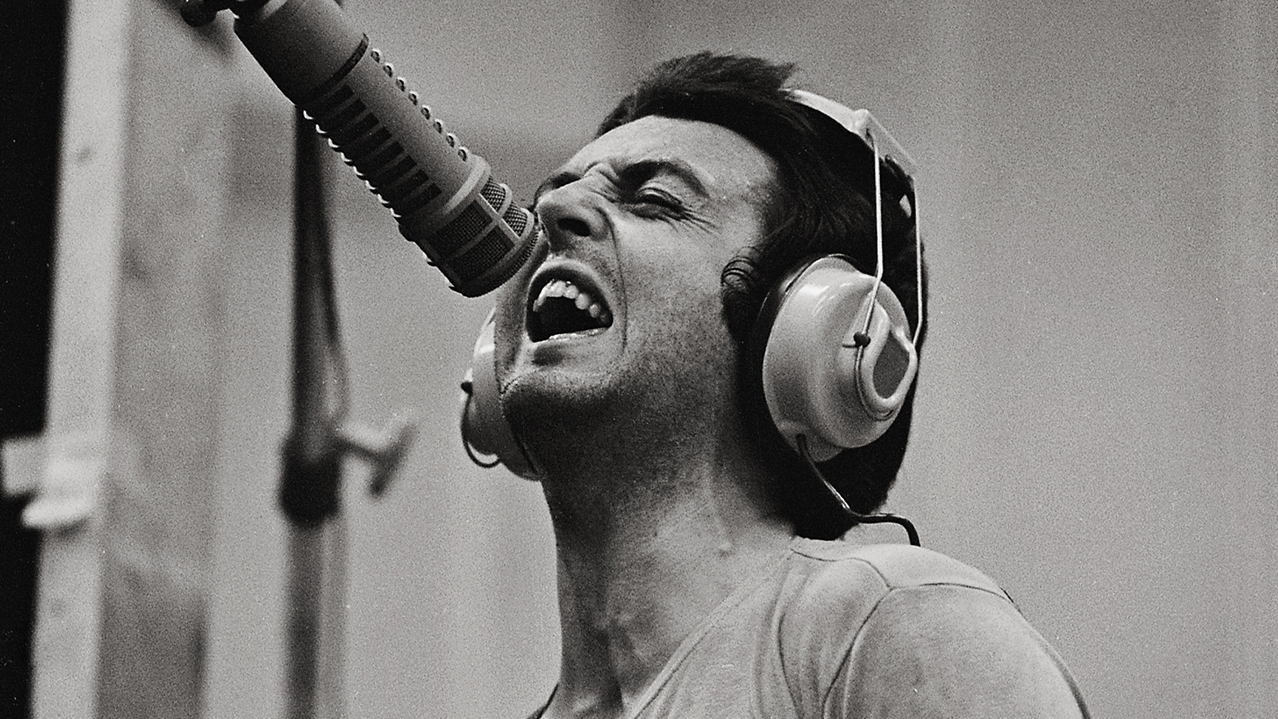

An acquaintance of mine once met Paul McCartney after a show and told him that he’d enjoyed the gig but he had a whole list of songs that he wished Paul had played. McCartney apparently just looked at him and said: “You’re not the first person to say that to me, you know.” None of which matters. Here you will find Paul McCartney, bearded and embattled, writing songs among the writs on a Scottish farm. Paul McCartney, sleeves up around his elbows, in MTV videos with Motown stars. McCartney filling stadiums in the 70s, writing about his old friend in the 80s, writing for wife Nancy Shevell, writing for Linda, writing with Youth and Denny Laine and Eric Stewart, working with Mark Ronson and George Martin and Nigel Godrich. Always playing, always writing and singing, ballads and rockers and dancefloor fillers and, above all, silly love songs. Every stage of his remarkable career, from those early post-Beatles days to his current status as the most respected songwriter alive, is here, and thank goodness for that.

Pure McCartney is a tasting menu, an immense, filling tasting menu, for a series of incredible albums, of which every home should have at least several, a reminder of a career that’s rarely stalled and is always flowing. Not every song is a classic, but so many of them are. (The proportion of singles to album tracks here is higher than on most boxed sets, because McCartney is to singles what pollen is to bees.) Start here, go back, and don’t stop.

David Quantick is an English novelist, comedy writer and critic, who has worked as a journalist and screenwriter. A former staff writer for the music magazine NME, his writing credits have included On the Hour, Blue Jam, TV Burp and Veep; for the latter of these he won an Emmy in 2015.