You can trust Louder

When Paul Weller, 59 this year and four decades a pop star, wrote Changingman, it seemed a touch ironic, because in the 90s Weller was in a musical rut, releasing a stream of samey modrock records. It was easy then to forget that Weller had once, in both The Jam and The Style Council, been eager to take on all kinds of music, from the artpunk of Wire to the guitar funk of The Isley Brothers. And then, as the new millennium kicked in, Weller got his imagination back. The same restlessness that had caused Weller to split up The Jam at the height of their fame and move into uncharted waters – the same restlessness that led him to abandon the Style Council’s jazzpop stylings and make an acid house album that his record company refused to release – was the same restlessness that enabled Weller to be the only one out of all his punk contemporaries to lurch into an entirely new direction in the 21st century.

The records he was making in the new millennium contained beats and loops, and a new ferocity and sense of commitment that had been missing during the Modfather years.

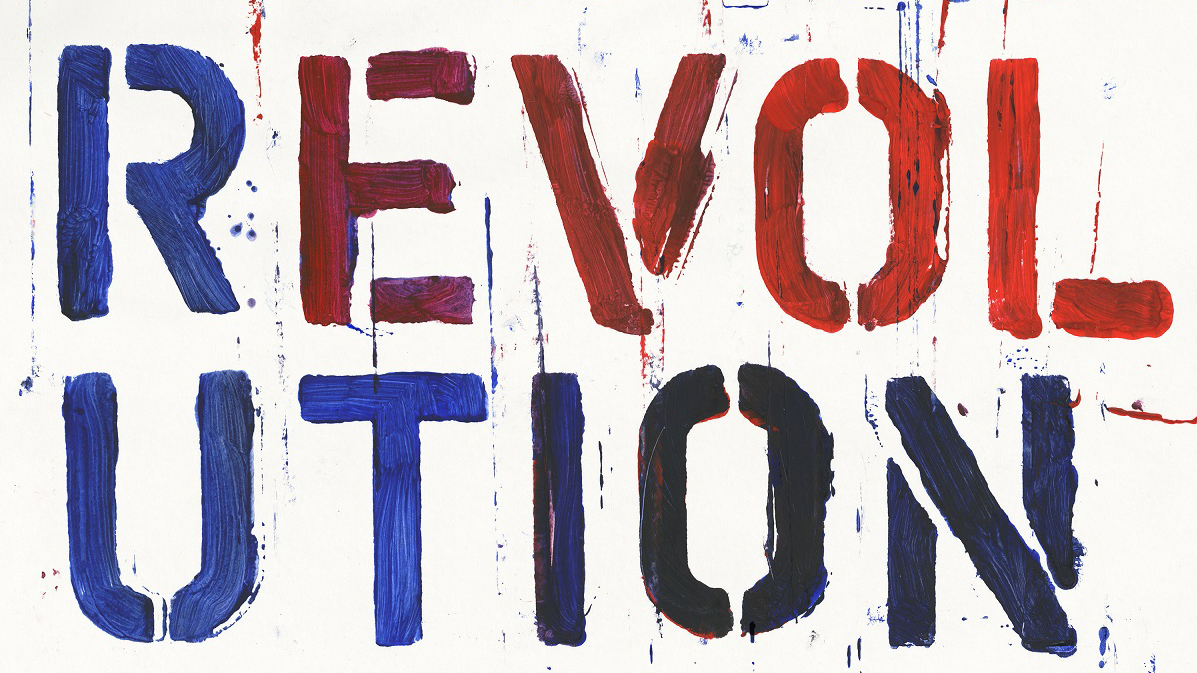

At times, albums like 22 Dreams and Sonik Kicks also sounded quite harsh, as though the singer was trying to invent his own musical brutalism: but now, with A Kind Revolution (the title a sort of peace-and-love suggestion from Weller), Paul Weller has made possibly the most melodic record of his recent career. Not since the pop flights of The Style Council have their been so many great tunes on a Weller album: from She Moves With The Fayre, whose Robert Wyatt guest-vocal gives it an oddly Canterbury Scene-like atmosphere, to the gospelly The Cranes Are Back, these are songs which, for the first time in a while, see Weller aiming for the beautiful rather than the agitated.

Every song is a standout: the opener Woo Sé Mama (with backing vocals by PP Arnold and Madeline Bell) is happy enough and New Orleansy enough to pass for Dr John in a very good mood, while the ballad Long Long Road is a distant cousin of both Let It Be and The Dark End Of The Street. Best of all is a guest vocal from a throaty soul singer who turns out to be Boy George (there is a slight surreal brilliance to the contributors: sadly Marilyn does not offer a bongo solo). And all these tunes are backed up by a band who seem, like Weller, to be really enjoying themselves.

At an age when most artists are keener to trudge up and down the nostalgia circuit, making albums that even they don’t want to listen to, Paul Weller is enjoying an enviable creative resurgence. Let’s hope it never stops.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

David Quantick is an English novelist, comedy writer and critic, who has worked as a journalist and screenwriter. A former staff writer for the music magazine NME, his writing credits have included On the Hour, Blue Jam, TV Burp and Veep; for the latter of these he won an Emmy in 2015.