You can trust Louder

For a band whose career was largely defined by the scale of their ambition, it’s a little perplexing to find Pink Floyd slipping into their senescence by releasing The Endless River, an album of pleasant but unspectacular ambient noodling.

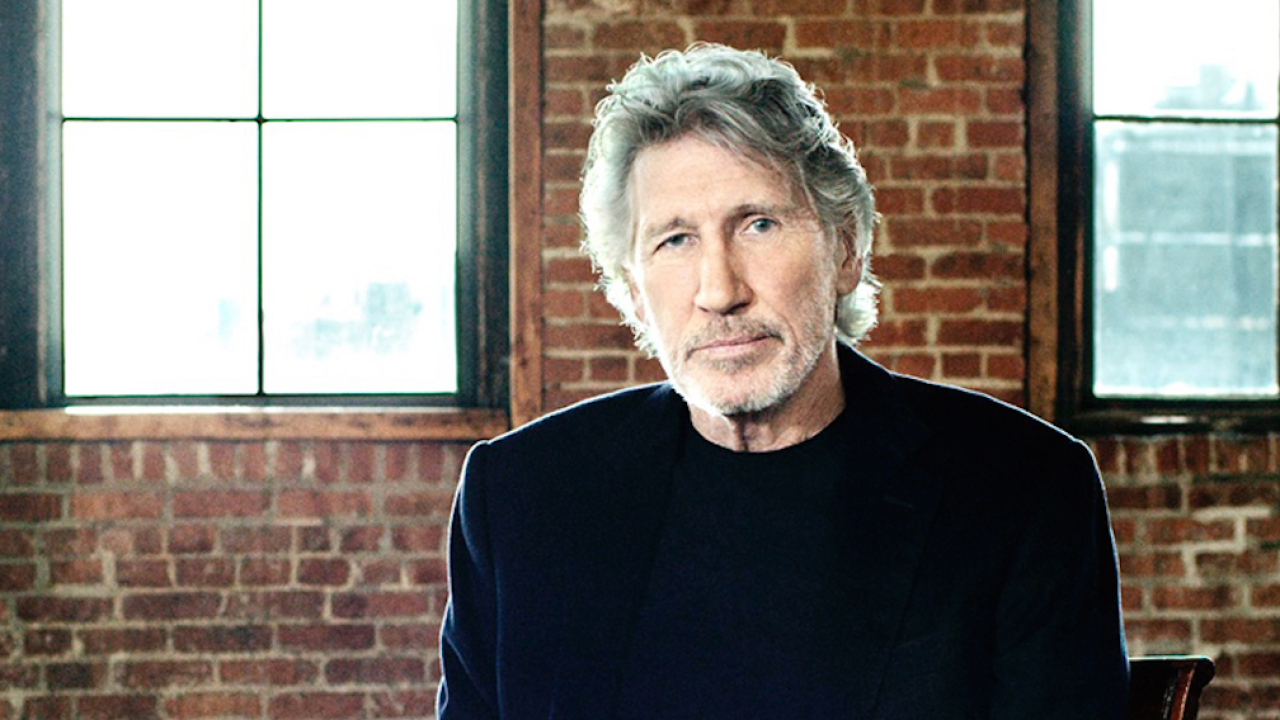

Meanwhile, Roger Waters (who’s three years older than David Gilmour, don’t forget), finished a three-year, 219-date, cash-harvesting tour in September 2013, then spent the best part of a year turning it into an equally ambitious film. Or, to give it a more precise description, an equally ambitious film of the tour of the other film of the original album.

Roger Waters: The Wall is two films in one. The first is the concert film, and it’s undeniably epic. The production is breathtaking, the performances immaculate, and the impact of songs like Run Like Hell and Comfortably Numb remains undiluted.

The latter is especially powerful, as the camera focuses on the euphoric faces of audience members clearly affected by what they’re witnessing. As live footage goes, it’s an extraordinarily emotional few minutes. Elsewhere, planes appear to crash into the stage, pigs do fly, Gerald Scarfe’s animations still terrify, and Waters strafes the audience with a convincing-looking machine gun.

The second film within the film is a more personal one as Waters does a grand tour of Europe in his Bentley, in search of graveyards and gravitas. It’s a curious affair. He takes his children to the site where his grandfather is buried. He ponders the significance of a lightning strike on Mount Olympus with travelling companion Andrew Rawlinson, a Cambridge scholar who accompanied Waters on a similar road trip when they were teenagers. He drives past executions and refugees. He cries, the camera lingering over his wet cheeks. He gets drunk, alone, in a bar. And he plays his trumpet at war memorials, alone apart from the camera crew documenting it all.

The generation that never spoke about what they suffered and what they saw has been ceded by another that makes big-budget films attempting to make sense of how they feel about it all. But it’s a testament to the filmmakers that this most personal tale – which in less skilled hands could have been rendered as a vapid exercise in navel-gazing – dovetails so comfortably with the vast, intensely communal nature of the dazzling live footage. Just make sure you see it on a big screen.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

_ _

_ _

Online Editor at Louder/Classic Rock magazine since 2014. 39 years in music industry, online for 26. Also bylines for: Metal Hammer, Prog Magazine, The Word Magazine, The Guardian, The New Statesman, Saga, Music365. Former Head of Music at Xfm Radio, A&R at Fiction Records, early blogger, ex-roadie, published author. Once appeared in a Cure video dressed as a cowboy, and thinks any situation can be improved by the introduction of cats. Favourite Serbian trumpeter: Dejan Petrović.