"As kids, we’re not taught how to deal with success,” philosophises Charlie Sheen. “We’re taught how to deal with failure. If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. But if at first you succeed, then what?” Indeed, then what? Take Slash, for example. Here’s a man whose old band’s first album sold 14 million copies in the US alone, shaped the tastes of a generation, and set the bar high for an entire genre. How do you deal with that?

What could someone possibly learn from such a colossal, epoch-defining triumph, except that to tweak the formula would be foolhardy at best and perhaps suicidal? To compound the issue, the songs that prompted the sales are now so ubiquitous they’re part of the air we breathe, so familiar that any new twist to the template prompts nostalgia for that initial triumph.

This, then, is one of the problems faced by Slash every time he records a new album, or works with a new set of musicians. It probably explains why Myles Kennedy is on board, not only as the owner of an extraordinary set of pipes but also for his ability to mimic voices that preceded him: the small-town howl of Axl Rose and Scott Weiland’s crackling, sinister baritone.

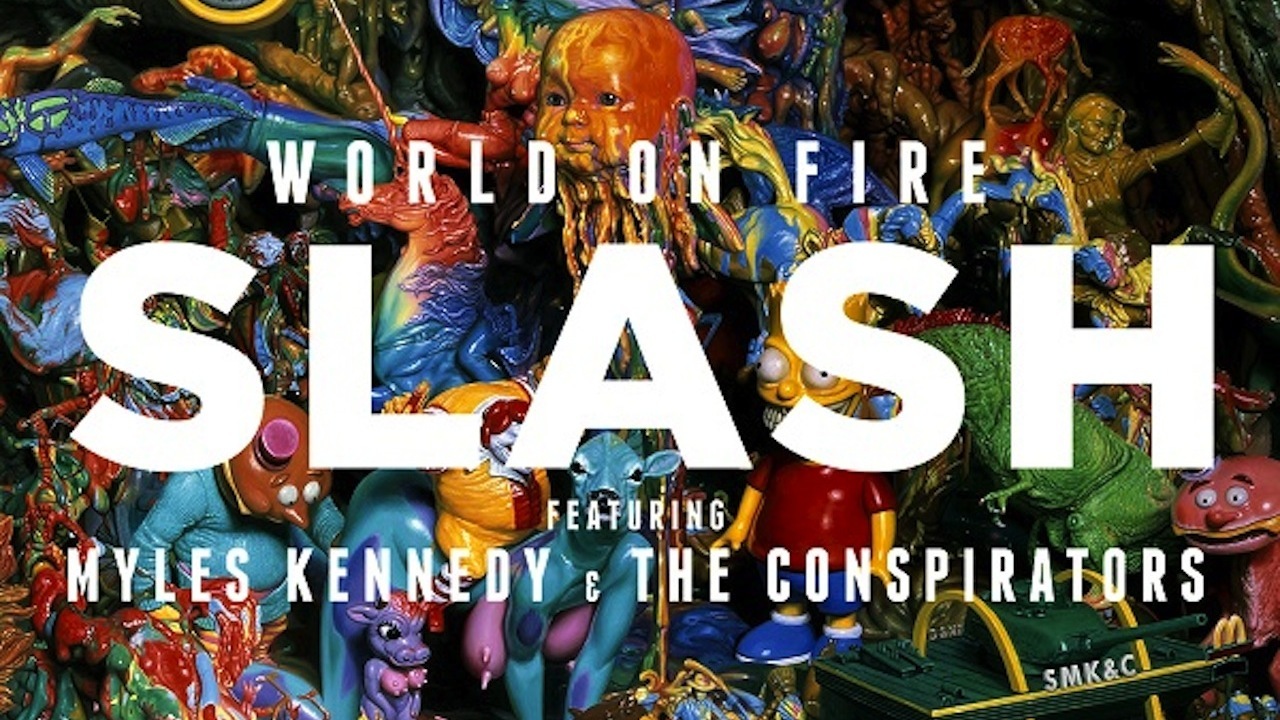

It’s not the only problem Slash faces every time he records. As the loudness wars show no sign of approaching an armistice, let alone a lasting peace, rock albums are increasingly mastered like pop and R&B collections, with everything as loud as everything else. Gone are the dynamics, the subtleties, the light and the shade, all lost to the overworked evils of compression and equalisation. This means that an album as ambitious as World On Fire – and, at 77 minutes, WOF is nothing if not ambitious – becomes a never-ending sonic wall one is required to forcefully dismantle in order to figure out if what’s on the other side is worth visiting. Faced with this kind of exhausting bombast, you can see why Noriega surrendered.

So it’s a terrible album, right? Wrong. WOF is a very, very good record. Once you’ve taken a mental wrecking ball to all that brickwork and worked your way past the songs that play tricks on the memory – the cowbell on the title track that channels Nightrain, or the drum-heavy intro to 30 Years To Life, which immediately triggers thoughts of Paradise City – this is a vibrant, utterly ferocious set of tunes. It’s as if Michael Bay were in charge, choreographing and corralling everything for maximum explosive effect. It’s relentless, it’s exciting, and from time to time it even feels a little bit dangerous.

It also helps that the two main players are so transparently on top of their game: Slash is still the master of those sleazy, slithering, fleet-of-finger riffs, and much of his soloing sounds like he’s possessed, firing off cascades of notes with a dizzying, effortless precision. Kennedy’s performance is similarly frenetic, and while his lyrics may occasionally baffle – just what, pray tell, is a ‘ten-tonne suicide’? (Automatic Overdrive) – the range of the man is little short of breathtaking. Take Wicked Stone: it rattles along at the kind of merciless pace that would turn most decent singers into feverish, gibbering loons, but Kennedy glides above it all with diabolical ease.

It would be easy at this point to assume that this a triumph for technique, a conspicuously talented group of musicians relying on their skills to paper over cracks elsewhere, but that isn’t the case. The instrumental Safari Inn is a rather dreary jam, but it’s the only weak spot. This is music for arenas, with huge moments everywhere. Try the big chorus on Bent To Fly. Or the big chorus on The Dissident, with a ‘whoa-whoa-whoa’ section perfectly designed for audience participation. Or the big chorus on… you get the idea.

So much of the album is in-your-face epic that it’s perhaps no surprise that the three best tracks are also the longest. Beneath The Savage Sun starts out all Alice In Chains and ends like Metallica. Battleground gently drifts from ballad to crunching rocker and ends in an enormous, Mott The Hoople-style singalong, and The Unholy is a Stargazer for the 21st century.

I’ve never subscribed to the view that music should really mean anything, but it should make you feel something. In that respect, World On Fire succeeds wildly. Listening to all 17 tracks in one go feels like going 12 rounds with a heavyweight boxer, a championship belt on the line. It’s a brute, it hurts, it’ll pin you against the ropes… but persevere and the rewards are worth it.