When Ted Leonard first took over vocal duties for Spock’s Beard’s 11th album, 2013’s Brief Nocturnes And Dreamless Sleep, most listeners were enchanted by the results. However, some stuck fast to scepticism. A few online moaners suggested he had single-handedly turned the modern prog superpower into a pop band, with nasty things such as tunes and choruses. To them he was the Phil-Collins-ruining-Genesis of the 21st century.

A few online moaners suggested he had single-handedly turned the modern prog superpower into a pop band, with nasty things such as tunes and choruses. To them he was the Phil-Collins-ruining-Genesis of the 21st century.

Well, much as Collins was never the catalyst in Genesis becoming more accessible (the whole band evolved that way), and just as that group’s records became different but (at first) equally brilliant, so Leonard stood falsely accused. He’s been moved to defend himself on You Tube, pointing out that the post-Neal-Morse-era Spock’s Beard functions as a democracy, and that the tracks he’d written that the naysayers were criticising had been chosen by Alan Morse.

“We collectively liked the songs and so we recorded them,” he wrote. “That’s what the band is all about. Like it or not, I am part of this band. I’m the biggest fan in its history, and we will forge ahead…” He added, “Selling out? Piss off!”

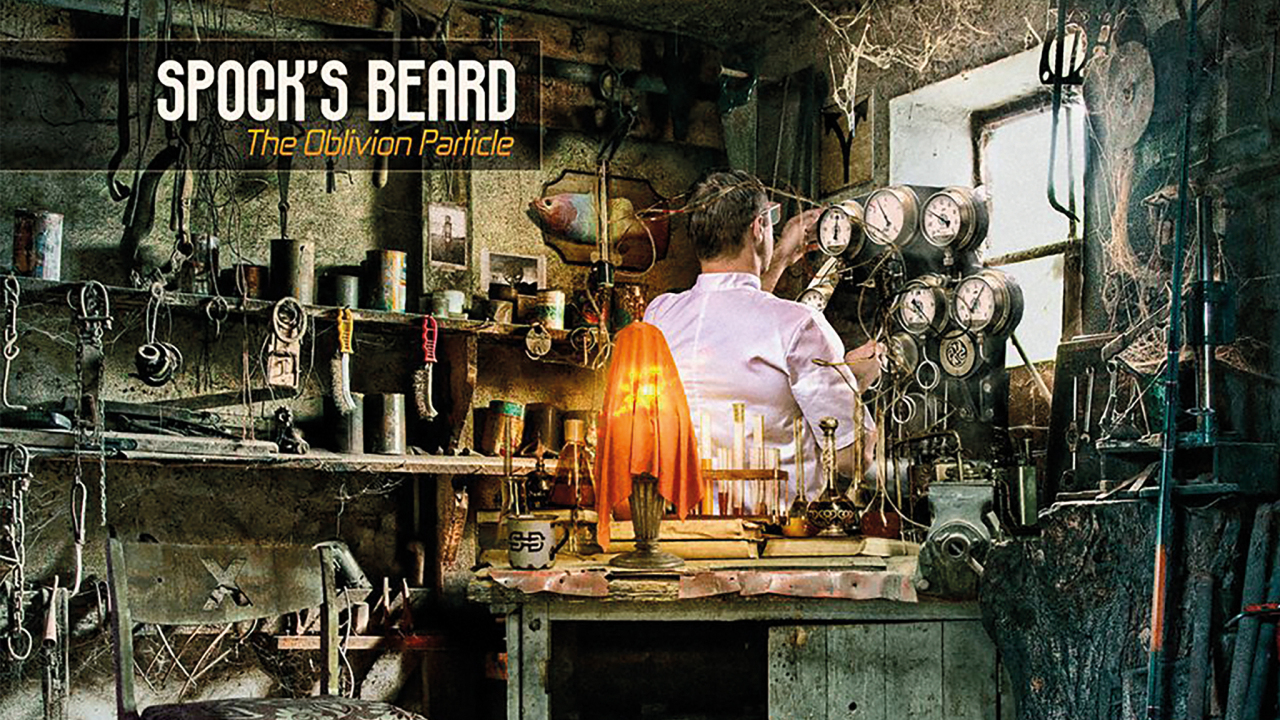

His melodic rock background fused firmly with the unit’s meandering musical template on what some cite as the best record of their 23-year career. So if you liked Brief Nocturnes, you’ll thrill to The Oblivion Particle. The West Coast wizards of harmonies, counterpoints and graceful structures (which do just enough to keep you guessing, without actually tripping you up) deliver their dozenth dynamic salvo with a meniscus of smooth on top.

It glides through its 66 minutes with a becoming mix of muscle and mystery.

They don’t desert their essence, but they do focus on the present as well as the past. (As Spock himself said in Star Trek, “Change is the essential process of all existence.”) And the results will surely silence any remaining doubters out there. The Oblivion Particle glides through its 66 minutes with a becoming mix of muscle and mystery.

Tides Of Time, the slick, subtly shifting opener, lets you know you’re in safe hands right from the start, although the kind of safe hands that keep complacency at bay by juggling you over a fireplace every now and again. With dashes of Dance On A Volcano, it whirls chunky rhythms from Jimmy Keegan and Dave Meros, dramatic keyboards and Alan Morse’s climactic shredding guitar into a stormy sea.

Minion begins with vocal harmonies that smack of Kansas’ Carry On Wayward Son, before a heavy AOR riff serves as a decoy to allow in a sorrowful piano break. Ryo Okumoto stars here. Then there’s Hell’s Not Enough, a ballad that’s expertly maintained at a controlled level of hysteria, like Muse trying on a straitjacket.

The instant standout is Bennett Built A Time Machine, a resonant pop-prog time travel tale with fine vocals from Keegan. Our hero heads back to New York in 1983 to ‘reinvent his future, unmake mistakes, unseal his fate’ as an irresistible chorus drops into a throbbing bass-led midsection. This then builds into something not entirely dissimilar to Pink Floyd’s On The Run, and the band are flying. Even the instrumental passages on The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway come to mind. While most of the album is certainly solid, never dipping below ‘impressive’, here Spock’s Beard are in the zone.

The barriers of linear time thus conquered, they move on to Get Out While You Can, which carries a slightly ominous sense of foreboding. ‘Judgment day is here,’ sings Leonard, without revealing whether the refrain is or isn’t a Philip Larkin reference. The Center Line then ups the ante on grand cinematic flourishes, and the 10-minute To Be Free Again lurches from jerky to thundering to looping reveries.

If the first half of the album feels too much like AOR power-pop to you (in which case you have an extraordinarily low threshold for convention, and must loathe Supertramp, Toto, Elbow and Jellyfish), then the second half will placate your wandering ear. It’s all over the place: not as in ‘a mess’, but as in ‘okay, they’re really stretching the parameters here’. The finale, Disappear, is relatively becalmed, with Kansas violinist David Ragsdale adding his touch.

The band’s own time machine remains happily set to deploy the best of what’s been, and also of what’s beyond. Spock’s Beard are continuing to forge ahead, and their first album since Leonard Nimoy died will see them, logically, prosper.