Here come the prog rock faithful, an army of gatefold-sleeve connoisseurs converging on Sheffield City Hall like punk never happened. The musical siren tempting them out on this brisk evening is a live set by Steve Hackett, including a hefty slab of vintage Genesis tunes first recorded four decades ago. It’s an impressively decent crowd for such a specialist show, almost filling the Irwin Mitchell Oval Hall, a handsome three-tier auditorium with a capacity nudging 2,300. And tonight they’re going to party like it’s 1976.

In the bowels of the City Hall, Hackett is signing autographs, posing for selfies and chatting with meet-and-greet fans. Genial and discursive, he introduces Classic Rock to his charming third wife and touring companion Jo Lehmann, a writer who occasionally contributes lyrics and vocals to his music. Apologising for the lack of rock-star excess backstage, Hackett quips that his dressing room habits are “more ovaltine than overdose” nowadays.

At 67, unlike many veteran rockers, Hackett doesn’t find touring a chore. “I’m a volunteer,” he nods. “It’s civilian life I find more of a grind. When I’m on the road I feel like I’m doing what I’m designed to do. It’s like a racehorse loves to run. The test is against personal energy, but I deliberately do rehearsals so I can function when I’m in a coma, when I haven’t had enough sleep. So when I’ve had a 24-hour flight to Australia, the idea is that muscle memory takes over.”

This year alone, Hackett’s live schedule has been packed solid, with dates across America, Europe, New Zealand and Australia. More shows in the Far East are also on the cards, and he’s even in discussions about his first ever dates in India. Between shows, he and Jo have recently travelled to China, Thailand and Cambodia. “We’ve been able to tear off huge chunks of the world,” he says.

The audience tonight is mostly male and mostly middle-aged, though there’s also a small but significant female contingent. Some of the younger women look like they may have been dragged here by their dads, but Hackett insists prog’s blokey reputation is undeserved. “There’s this idea that this music mainly appeals to middle-aged blokes, but I don’t see it like that,” he protests. “I look out over the audience sometimes and I see it’s fifty-fifty. Maybe the atonal stuff doesn’t turn on women so much. A lot of progressive acts where the instrumental side is so impenetrable, that might not have the benefit of memorable melodies. But I think a lot of the Genesis stuff from the seventies is very romantic. I don’t think it’s music that was deigned to exclude women.”

Of course, Hackett recognises that prog remains a dirty word to some. But he also points out how the albums made by the late-period Beatles and early David Bowie could be deemed progressive. Even so, he gets the joke. He even enjoyed the recent BBC spoof sitcom Brian Pern: A Life In Rock, which affectionately satirised Genesis at the height of their Peter Gabriel-fronted pomp.

“They asked me to take part and I was going to, but I was too busy rehearsing,” Hackett nods. “It was really about the trappings of that period, the bell‑bottoms aspect, specifically early Genesis and Peter’s theatrical persona. But that’s what got us on the covers of music magazines.”

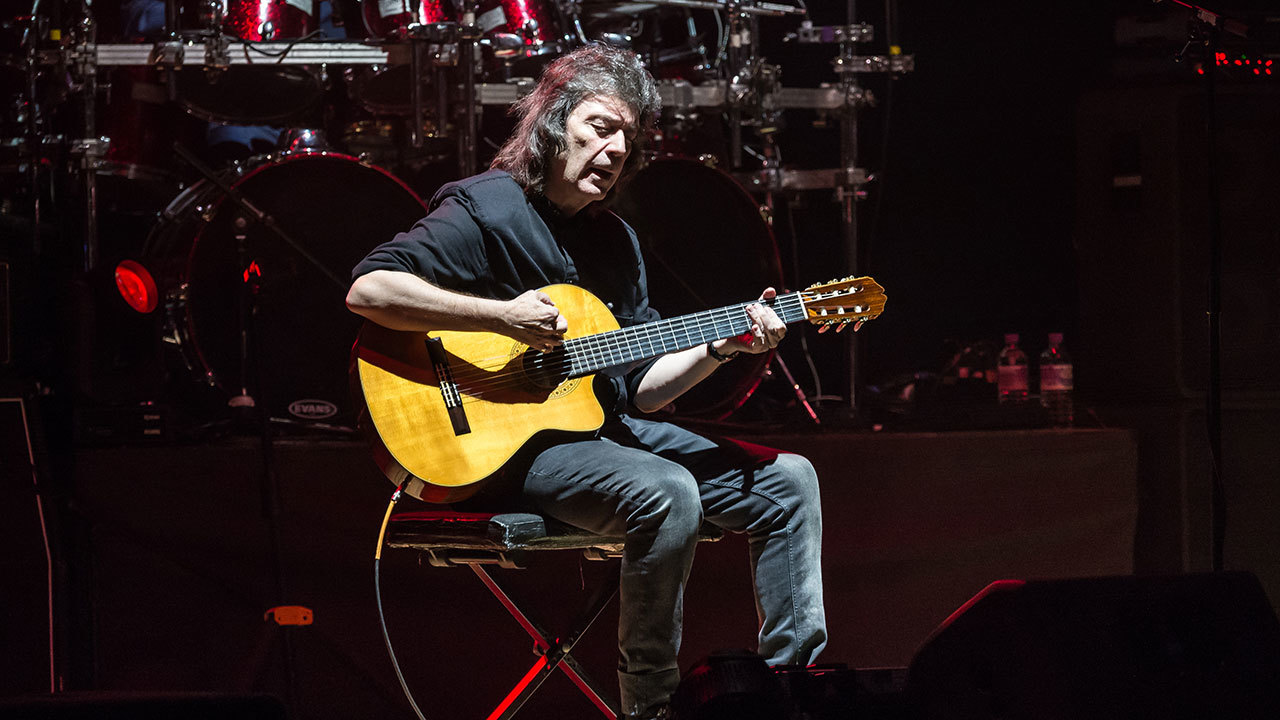

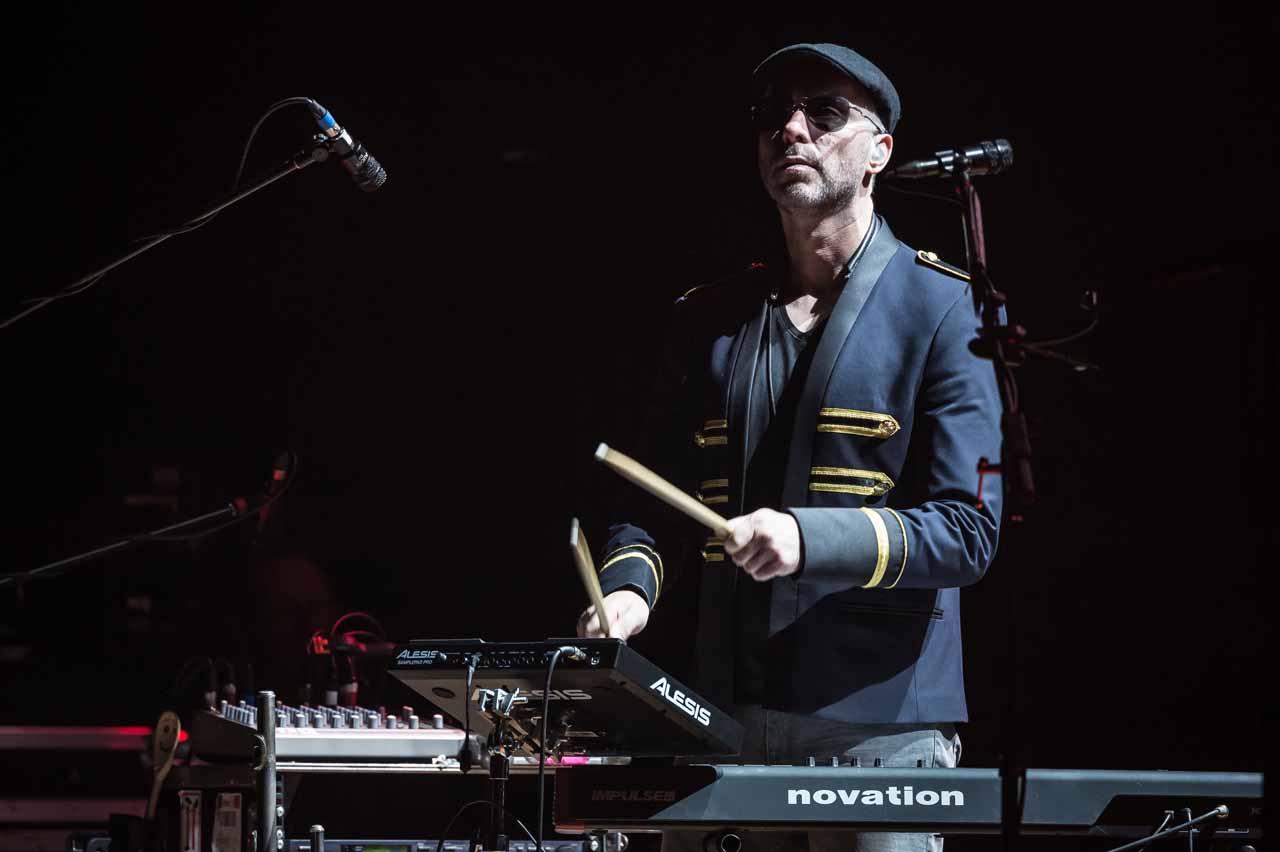

Showtime looms in Sheffield. Hackett takes the stage, flanked by his regular core team of drummer Gary O’Toole, keyboard player Roger King and saxophonist Rob Townsend. A recent addition to the band, on bass and twin-necked guitar, is the towering blond figure of Nick Beggs, formerly of 80s synth‑pop chart-toppers Kajagoogoo. The church of prog has a broad roof.

The opening set, subtitled Classic Hackett, features an hour of material spanning his prolific catalogue of post-Genesis solo albums. His latest release, The Night Siren, is showcased prominently and leans pleasingly towards unabashed, combustible heaviosity. An early standout is El Niño, a poundingly percussive thunderstorm of War Of The Worlds bombast, marbled with cascading, filigree guitar lines. It’s rousing stuff, and a lusty rebuke to the cliché of prog as cerebral jazzwank noodling. Likewise In the Skeleton Gallery, another muscular beast that prowls and growls from the shadows, shape-shifting in tempo and texture.

Introducing another new album track, Behind The Smoke, Hackett makes a short explanatory speech linking the current Middle East refugee crisis with his own distant family history of fleeing pogroms and persecution in Eastern Europe. Smouldering and seething, the tune snakes along on a vaguely Arabic-sounding melody and a hard-driving shudder-riff that unavoidably invokes Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir.

Winding back more than 30 years, Hackett slips into more stately mode for long‑standing live favourite The Steppes, a billowing cloudscape of intertwined guitar, sax and keyboard melodies laid over a steady metronomic beat. Nervously eyeing the crowd afterwards, he quips: “So many pals here, all giving me marks like Russian judges.”

Another highlight of this opening act is Serpentine Song, a wistfully nostalgic elegy suffused with the sepia-tinted lyricism of vintage Ray Davies. Hackett’s younger brother John, once a regular band member, now an occasional guest, joins him onstage to play flute on the track, a joint tribute to their late father Peter.

“He was a man of many parts, many skills,” Hackett says before the show. “I’ve often said I could have had twenty different professions out of the skills he possessed. He became an artist by profession – he turned professional at the same time I became a professional musician, around 1970-’71. He was making enough money to support the family by selling paintings along the railings of Bayswater Road in London, near Hyde Park. I think he sensed that song was a bit of an obituary to him, even when he was still alive.”

The solo set climaxes with Shadow Of The Hierophant, taken from Hackett’s 1975 debut solo album Voyage Of The Acolyte, recorded while he was still in Genesis. Though usually performed with vocals, tonight the track becomes an 11-minute instrumental colossus of key-changing, fretboard-tapping, cacophonous avant-rock excess. By the fiery finale, Beggs is on his knees, bashing at effects pedals with his hands, while waves of shuddering noise reverberate around the auditorium with a deafening clang.

“That’s the last of the quiet ones,” Hackett grins as the dazed-looking crowd stumble out to the bar for interval drinks, ears ringing and teeth rattling.

Hackett returns after a short break to play a second, longer set subtitled Genesis Revisited. Between solo releases, Hackett has been reworking his old band’s back catalogue on album and stage for two decades. For this tour, his focus is on Wind And Wuthering from 1976, a loose 40th-anniversary celebration of the final album he made with Genesis before quitting to go solo. From a quick straw poll among the Sheffield crowd, it becomes pretty clear that Wind And Wuthering is not deemed a classic by the average Genesis fan. But Hackett bristles at any suggestion it may have been overlooked and underrated.

“I can’t tell you exactly what that album has sold over time, but it’s millions,” Hackett insists. “I know the writers can sometimes be dismissive of some of that stuff, but I think the true owners of the songs are the audience anyway. So no, I think it had its due then and it’s having its due all over again now, because the response is so strong to that material. It’s much‑loved stuff.”

So complex and exacting are the arrangements in many of the early Genesis tracks, Hackett says it takes him three months to relearn a full set.

“I’ve written stuff that’s more technically difficult since,” he says, “but I find the Genesis stuff is basically all over the place. It’s not logical; it doesn’t necessarily fit on the guitar. You have to remember a lot of shapes – that’s how it works with me. Once you’ve done a few shows, everything’s possible. But first of all I go into this nervous breakdown mode, putting it off and putting it off, and then I’ve got to cram it last minute. There’s no point rehearsing it too early – it’s not going to stay with me.”

During this second act, the band line-up expands to include Swedish singer Nad Sylvan, who has been lead vocalist on Hackett’s Genesis-themed tours and albums since 2012. A striking androgynous figure in colourful robes and flaxen locks, Sylvan appears to have beamed directly down to south Yorkshire from his golden space pyramid hovering just beyond the outer rings of Saturn. Good effort. Sylvan’s vocal timbre also sounds uncannily similar to Peter Gabriel’s in places, lending an oddly counterfactual dimension to the Wind And Wuthering tracks, which were originally voiced by Phil Collins soon after Gabriel left Genesis.

The Swedish singer brings a sense of drama to the vaulting historical epic Eleventh Earl Of Mar, the doomy religious fable One For The Vine and the sprawling jazz odyssey …In That Quiet Earth. But he cedes vocal duties for Blood On The Rooftops to drummer Gary O’Toole, whose rich, baritone croon adds an extra warm-blooded radiance to Hackett’s flamenco-style flurries.

The band move beyond Wind And Wuthering for a final suite of Genesis classics, a marathon sprawl of trills, fanfares and baroque twists that includes Dance On A Volcano, Firth Of Fifth and The Musical Box. All receive a rapturous welcome. But there’s more propulsive bite in Hackett’s 1980 solo number Slogans, a bracingly fierce blast of skronking avant-rock, jazz-metal fusion that he saves for the encore.

This may sound like heresy to vintage prog fans, but Hackett’s solo tracks provide the real peaks of this show. They’re heavier, darker and more ambitious than the Genesis songs, which mostly sound like over-ornate museum pieces.

After the show, Hackett explains his kid-glove approach to his former band’s canon, sticking as closely as possible to the seventies blueprints.

“I don’t want to ruin people’s childhoods,” he nods, only half joking. “You’ve got to be reverent and do things that are authentic. We could zoom a million miles away, do a jazz improv based on this stuff, or a series of orchestral suites, as people have done. But as the co-author of this music, I feel the need to honour it in people’s memory.

“It’s easier with my own stuff. If I do El Niño and I’m firing off salvoes with a fast guitar solo, I can change that, I do it differently every night. But that’s new material and its mine. With Wind And Wuthering, it’s not really about impulse. There’s tons of form in there and I think you’ve got to honour that.”

A few days after the Sheffield show, I next talk to Hackett in Manchester. Between tour dates, he says he’s setting off to visit Haworth, where Emily Brontë wrote Wuthering Heights, the novel that inspired the album title Wind And Wuthering. Later that same day, BBC Four broadcast a new documentary about Genesis featuring all members past and present, followed by an archive prog compilation. This kind of profile boost can only be good news for Hackett, and for the health of progressive rock.

Hackett notes that his backstage meet-and-greet sessions no longer just attract the old-time Genesis faithful, but also a younger contingent who turn out to be musicians themselves. The circle continues.

“The clue is they have hair a little bit too long, or a certain look, a certain energy that I feel off them,” Hackett nods. “I’m proud to say this is music that inspired people back in the day, and it’s still inspiring people now.”