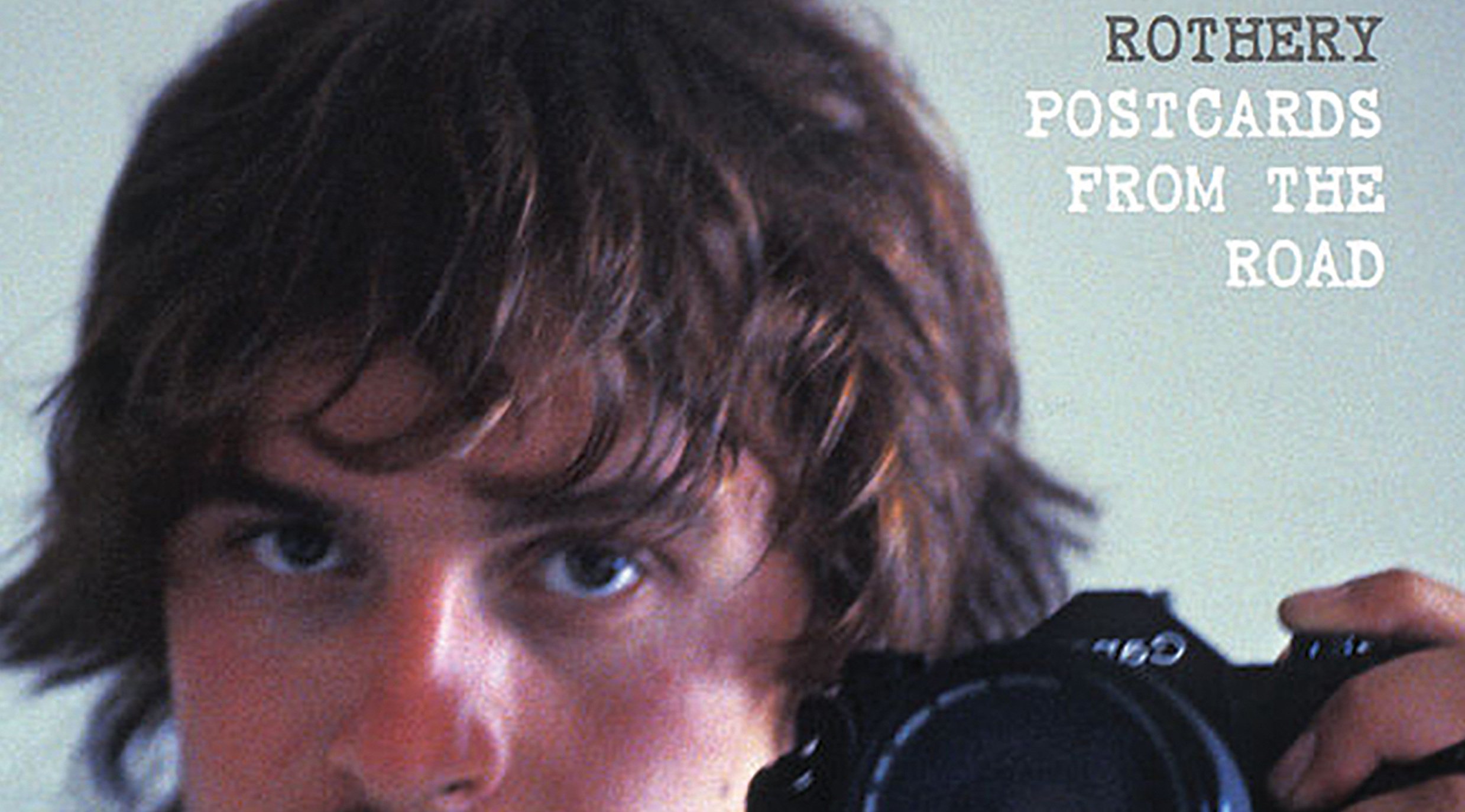

Fish sits reflected in quiet contemplation in a dressing room somewhere in Sweden on the Fugazi tour. It’s still early enough in Marillion’s career that the singer is applying the make-up that typified the band’s earlier performances. Off in one corner, Steve Rothery is fiddling with his ever-present camera. He gets a few shots and doesn’t think any more of it until he gets the film developed a few weeks later.

“That’s the one,” says Rothery, looking back on it now. “Fish putting his face paint on in the dressing room. That was the first photo I took where I thought I’d really captured a moment.”

Fish’s fixed gaze is here – in both black and white and colour – as is the young Fish, the flamboyant Fish, the hungover and grizzly Fish. Looking back at him through Rothery’s lens, he really does seem to be larger than life.

“Fish was easy to shoot because his moods were more variable,” says Rothery. “Everyone in the band is used to me pointing a camera at them but I’ve probably got the most photos of Mark [Kelly] gesticulating manically when I’ve pointed a camera at him!”

It’s sometimes easy to forget that Marillion came up by the traditional route: transit vans, minibuses, endless motorway miles and midweek gigs playing to disinterested crowds. These days everyone has a smartphone and its accompanying digital camera. Back then, it was down to someone like Rothery to capture the minutiae that goes to make up the day-to-day of a band. Luckily for Marillion (a recalcitrant Mark Kelly aside), not only was their guitarist embracing photography as much as he was the music they were making, but he also had a pretty good eye, as can be seen throughout this book.

He was consistent, too, so settings that would seem the most obvious to capture – the band being flown back from their tour on a Lear jet courtesy of EMI so they could perform Kayleigh on Top Of The Pops – are given as much credence as a slumbering Fish (he sleeps more than your average bear, judging by this collection), or a bemused-looking Ian Mosley, deep in conversation.

“I love the one of Ian talking to the priest,” says Rothery. “That was at the opening of a studio in the north-east in the mid-80s. It perfectly captures his personality.”

And that statement, perhaps, perfectly sums up exactly what this book is; moments caught in time, Rothery’s love letter to a far-off place from long ago, memories to be cherished and held forever.