As Chris Knowles points out in his brilliant collection of Clash opinions, Clash City Showdown, for a very long time The Clash was regarded as the band’s finest album. American music critic Robert Christgau called their debut “the greatest rock and roll album ever manufactured anywhere” and ranked it as the greatest long-player of the 70s, while UK music weekly Sounds voted it the all-time greatest album in 1985.

London Calling’s stature really began to rise after Rolling Stone voted it the greatest album of the 80s in 1989 (the US version of the album was released in January 1980). A cynic might claim that us poor saps have followed Rolling Stone like sheep in our subsequent re-appraisal of the album. It might be fairer to see it as a more balanced reaction to the album after the frostier reception it had on release.

In 1979, two years after their debut, the street-punk baton had been picked up by a ton of bands. Sham 69, Cockney Rejects, GBH and others were intent on having a white riot of their own. Fair enough, you could say. Working class white kids should be free to have their own music too – music that speaks to them about their concerns and their lives.

But from the outset, The Clash made it clear that they didn’t want that. White Riot was actually urging the white audience to join in, not do their own thing.

London Calling was neither a sell-out or a conscious attempt to crack America. But it can also be seen as a mature musical and political response to a British pop culture that had been transformed by bands like the Specials and Dexy’s Midnight Runners, and a bit of one-upmanship from a band at the height of their powers, encouraged to paint a richer picture by a man with a colourful background in rock’n’roll history.

Producer, Guy Stevens, had been a pivotal part of the 60s blues explosion, running Sue Records, smoking himself a whiter shade of pale with the likes of Procol Harum and Traffic. Stevens was the svengali behind Mott The Hoople (guitarist Mick Jones’ favourite band), had recorded early demos with The Clash and was on his uppers in 1979. Strummer and co dragged him out of the pub and into the studio.

Inspired by their deranged father figure, The Clash kicked out the jams in a new, more musical way. By London Calling, drummer Topper Headon could play anything. Paul Simonon no longer needed the notes stuck on the fretboard of his bass. Strummer and Jones were at the peak of their songwriting powers. The sky was the limit.

Train In Vain grooves like classic soul. Guns Of Brixton conjures up genuine London reggae. Rudie Can’t Fail was ska-punk in excelsis. The title track proclaimed a coming apocalypse – and welcomed it (‘London is drowning and I live by the river!’). This was the party at the end of the world. The Right Profile, Revolution Rock, I’m Not Down – the songs on London Calling are a righteous, raucous rave-up.

Recording a blistering version of Vince Taylor’s rockabilly classic Brand New Cadillac, Topper was dismayed at Stevens’ ecstatic reaction at the end.

“We’ll need to do it again,” said the drummer. “We speeded up.”

“All great rock’n’roll speeds up,” said Stevens.

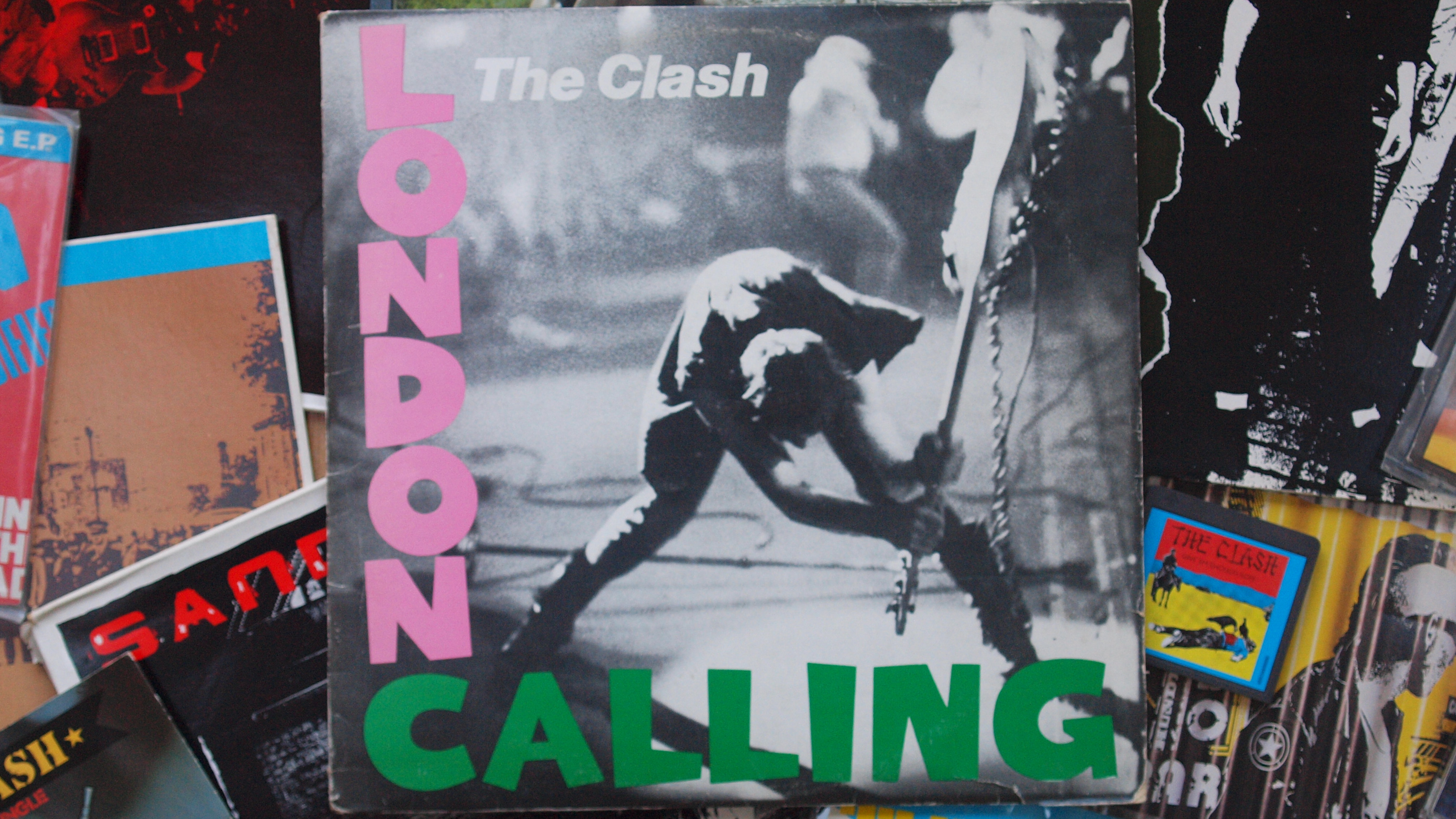

The Clash Albums Ranked From Worst To Best – The Ultimate Guide