The holy trinity of punk were so perfectly formed that it’s hard to imagine the scene without any one of them. The Pistols: searing and sneering, nihilistic and iconic (the artwork, the clothes). The Damned: the court jesters. Daft, tough, Tiswas-anarchic, a British Stooges/MC5. And The Clash: the guttersnipes and street punks, the voice you could relate to, and without whom it’s hard to imagine The Jam, Stiff Little Fingers, Sham 69 or Generation X, let alone Green Day, Rancid, or maybe even U2.

The Clash articulated the frustrations of working class kids in a way that the chin-stroking protest pop of previous generations couldn’t hope to, in a way that was more inclusive than the fury of the Pistols or the Damned’s goth theatre. (And, yeah genius, we know the irony: Joe Strummer went to a private boarding school and his father was a top diplomat. Hate to break it to you but David Bowie wasn’t really a spaceman, Tom Waits wasn’t a hobo and Ice-T didn’t really kill cops.)

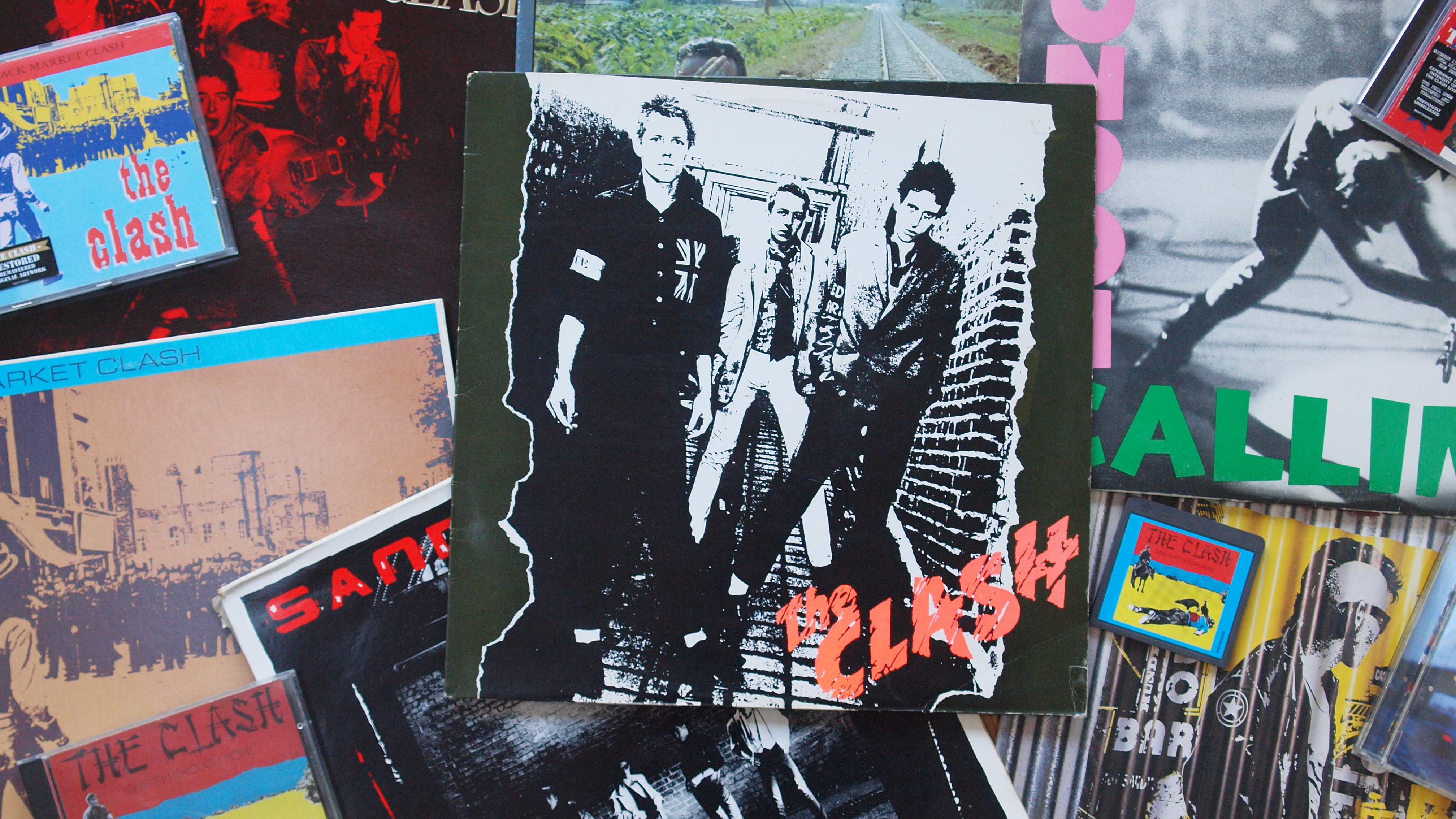

The Clash was hurriedly-written and recorded and it’s a messy and thrilling snapshot of two creative forces gelling for the first time. From their vocals (Strummer’s yobbish bark balanced by Jones’s boyish sensitivity) to their lyrics (famously, Strummer changed Jones’s track I’m So Bored With You to I’m So Bored With The USA), and even their guitar-playing (Joe’s choppy rhythm guitar versus Mick’s slightly weedy-but-melodic lead), the album is a true Strummer/Jones production. Both men were classic rock’n’roll dreamers. To find themselves in the right time and right place with the perfect partners must have been a buzz and, amid the anger and the outrage, the album captures that rock’n’roll woah perfectly.

Mostly The Clash talks about people in boring jobs, with annoying bosses, in a world going to shit. A London burning with boredom, where everyone sits around watching television. Where the TV is full of American cop shows, because killers in America work seven days a week. Where you get hassled in the street by cops and pressured to take a shit job down the Job Centre. Where ‘hate and war’ has replaced ‘peace and love’ and the world is full of cheats and junkies.

Sounds joyless? It’s only half the picture – a bit like describing Trainspotting as a movie about heroin addicts in Edinburgh. The Clash is full of defiance and dark humour and plenty of cheap thrills. Short adrenaline bursts like 48 Hours and Protex Blue (a stupidly laddish ode to the top condom brand of the time: ‘I don’t think it’ll fit my PD drill’) add levity to darker tracks like Deny and Cheat, while Janie Jones, Career Opportunities, London’s Burning and Garageland do all the heavy lifting – full of righteous anger, great one liners and gleeful humour. (Garageland, the witty riposte to Charles Shaar Murray’s earlier line that The Clash were a garage band “who should be left in the garage with the engine running”, isn’t bitter or spiteful but a warm salute to everyone who’s ever been in a dodgy band with ‘five guitar players, one microphone’ and an old bag of a neighbour who calls the police.)

Slap-bang in the middle of each side are two tracks about race that would define their career: White Riot and Police And Thieves. Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves single was released in the UK in July 1976, the perfect soundtrack to that year’s Notting Hill carnival riot and tailor-made for the Roxy, the punk club where Don Letts DJ’d, playing reggae and dub records (there just weren’t enough punk records to play all night and reggae’s outsider status meant it fitted perfectly). The Clash gave the song steel toe-capped boots and a knuckleduster to create punk-reggae, cementing a relationship between the two genres that continues to this day.

If Police And Thieves embraced multi-racial Britain, both musically and philosophically, White Riot was a little more singular. A two-chord rallying cry – rock music with all the blues stripped out of it (the album version is twice as fast and three times more furious than the laughably rinky-dink 7” version that came out just a month before in March 1977) – White Riot suggests that white people could learn a lot from west London’s black community, that if they too stood up against authority they could take over, instead of taking orders: ‘All the power in the hands/Of the people rich enough to buy it/While we walk the streets/Too chicken to even try it’.

Strummer’s lyric clearly admires the section of the black community that ‘don’t mind throwing a brick’ – the rioters pushed into confrontations by aggressive policing and refusing to take it anymore. Where White Riot becomes problematic is in the fact that its sentiments echo that of many far right groups. The National Front had similar views: that Britain was run by bankers (read ‘jews’) and white people should fight back and reclaim their country. Punk rock was a musical white riot – mostly white bands singing music (mostly) stripped of black influence – and a far-right and fuckwitted element of the Oi! movement made much mileage out of this.

If The Clash never really disavowed White Riot, they also never recorded anything like it again.

Police And Thieves showed where The Clash could go – not just deeper into reggae, but also into other musical styles – while White Riot was forever held against them as a reminder of where they came from by a punk audience who wanted their music to get more brutal, not more musical. It was a dichotomy that haunted the band throughout their career.

It split the audience and ultimately split the band too.

The Clash Albums Ranked From Worst To Best – The Ultimate Guide