It’s strange what has happened to rock time in the 21st century. The Jesus And Mary Chain haven’t made an album since 1998’s Munki, an album that was effectively sunk by Britpop and its aftermath, but 1998 feels like no time at all ago. It’s not like the difference between 1960 and 1978, more like the difference between, say, 1989 and 1995. As for the Mary Chain themselves, they have been around over 30 years, count as veterans, and yet given the vast number of veterans still at work they are very much junior rank. They still somehow feel, in other words, like a bunch of tousled-haired punks who are a long, long way from growing old. This is exacerbated by the fact that even into middle age, Jim and William Reid still argue like brothers forced to share a bedroom – indeed it was this fraternal fractiousness which accounted for the delay in the making of this new album.

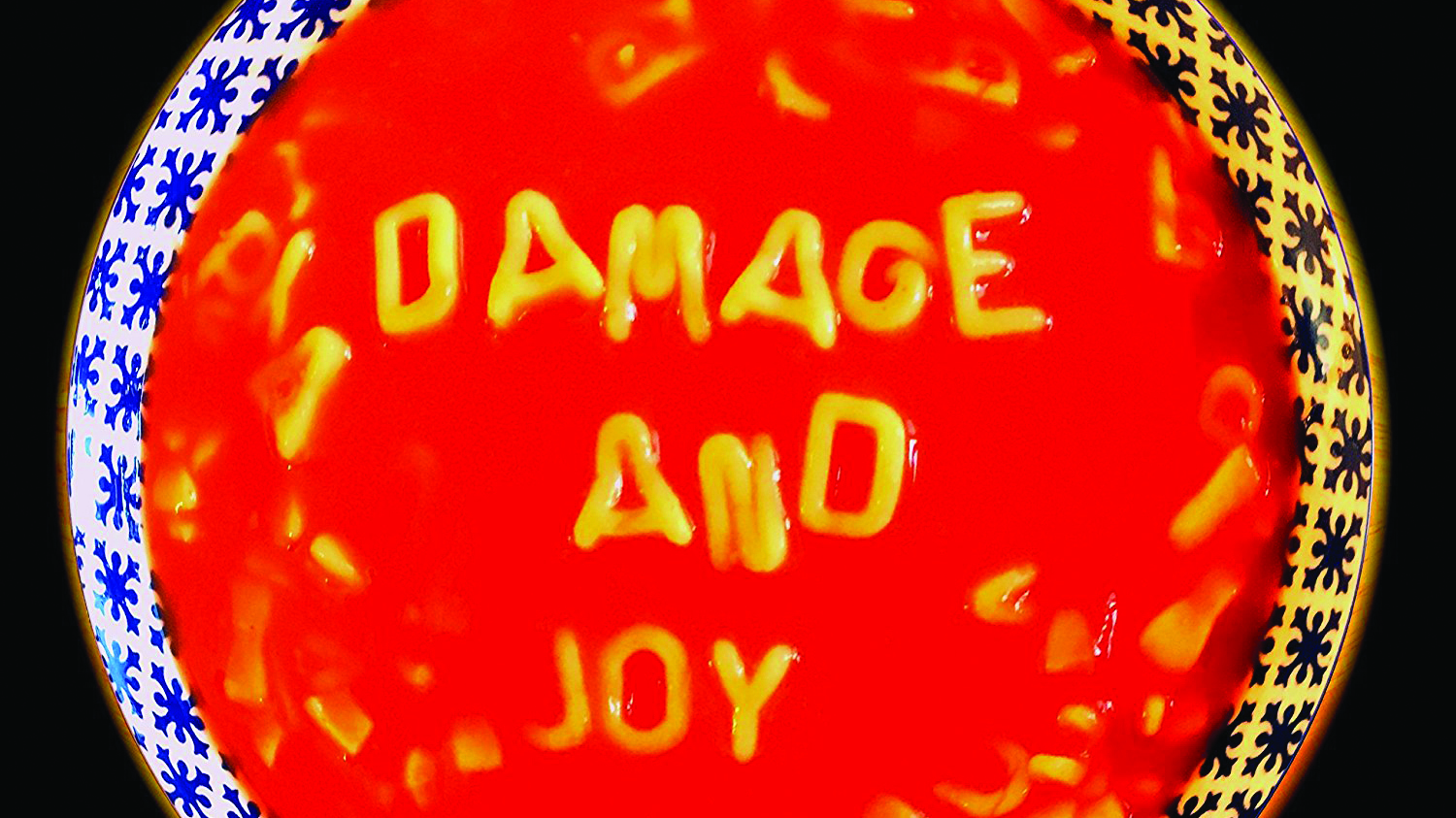

They also manage to get along sufficiently to continue, however, and Jim Reid has described Damage And Joy as representing a more “mature” Mary Chain. It’s perhaps more a case of a group who have experienced the passing of time, however – in many ways, they haven’t really changed at all, fans will probably be heartened to note, they’ve merely refined and honed their rock’n’roll dysfunction.

There are signs of experimentation: the stylophone-like scrawl that weaves through opener Amputation, with a riff that threatens to reprise Deep Purple’s Smoke On The Water, or the haywire Simian Split. There are some Krautrock tendencies, evidenced on War On Peace with its sudden, motorik quickening of pace. Meanwhile, Facing Up To The Facts is to Pere Ubu’s Final Solution what Sidewalking was to Cameo’s Word Up.

Mostly, however, this is (neo)classic Mary Chain, a group who have been neoclassical rockers for most of their career, harking back to the great tradition of elemental, caustic rock noir first established by the Velvets. Jim Reid’s lyrics are a roller-coaster of bipolarity: ‘Think I’m always gonna be sad,’ on Always Sad, convinced he will be fine on Mood Rider, reconciled to the emotional ride on Can’t Stop The Rock – ‘I’m falling and I’m happy.’ But the lyrics are clear-eyed rather than confused; he’s very experienced at being a Reid, and this album is as clear-eyed an expression of the JAMC condition as any they have produced. Kudos also for the female vocal contributions (on The Two Of Us, for example), offering a mirror feminine perspective.

This album is as good as we could expect from the Mary Chain in 2017.