You can trust Louder

This is the first Jethro Tull album of new material for 18 years – since 2003’s Christmas Album, to be precise. There have of course been plenty of Jethro Tull albums in the intervening years – live albums, anniversary reissues with copious bonus tracks, orchestral albums of Jethro Tull music frequently featuring Ian Anderson.

And then there have been Ian Anderson’s solo albums. Half a dozen of them. These include 2012’s Thick As A Brick 2 that expanded upon Tull’s 1972 classic, 2014’s Homo Erraticus that featured yet more adventures from Gerald Bostock, and Thick As A Brick: Live In Iceland.

Adding to the confusion is that most of the members of Jethro Tull also appear on Anderson’s solo records. All of which begs the question: what is the difference between a Jethro Tull album and an Ian Anderson solo album? The answer of course lies at the personal discretion of Ian Anderson.

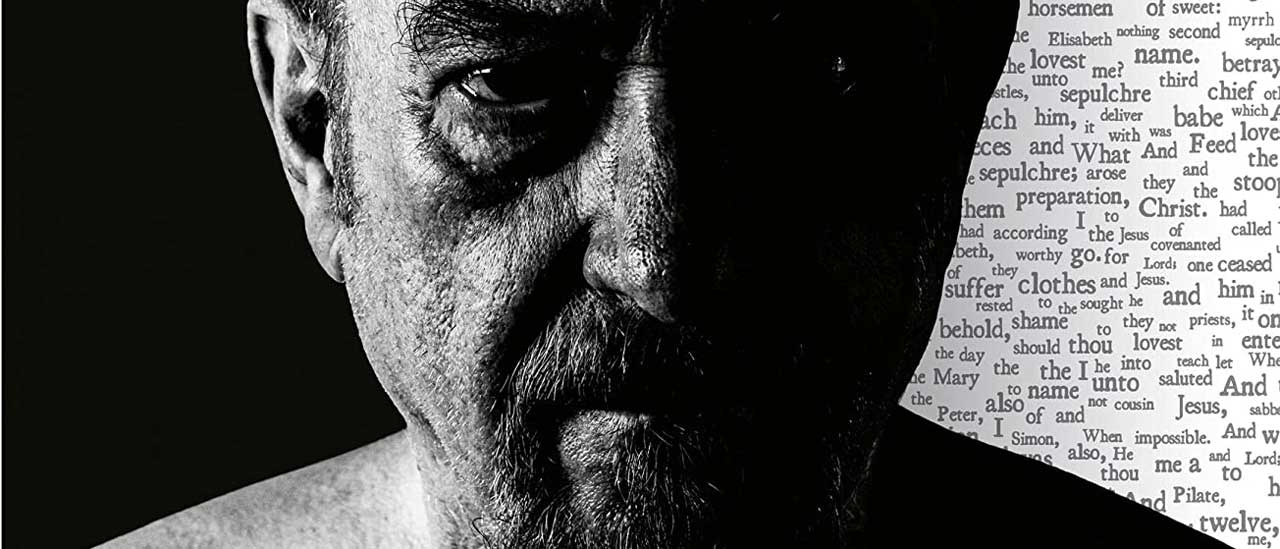

The Zealot Gene is a collection of 12 songs covering various aspects of the human condition. So no surprises there. There is a theme that binds them together, however: the Holy Bible. Each song title is followed by a reference to specific verses from the Bible that have spurred Anderson into lyrical action.

The connection is not always easy to make, and sometimes you’re better off just going with his words, although they can take some unravelling at times. But that’s all part of the plan.

The title track takes on Donald Trump and his populist ilk with their ‘dark appeal’ and extremist views, while album opener Mrs Tibbets surveys a pattern of wanton destruction and puts 9/11 in uncomfortable context. Still not sure where the Eccles cakes fit in, though. Less catastrophic but almost as disillusioning is the sight of teenage girls lying drunk in a gutter in a town centre near you in Sad City Sisters.

But it’s not all grim. Anderson remains an incurable romantic, alert to the voyeuristic pleasures of love on Shoshana Sleeping and its varieties on Three Loves, Three. He wraps it up with a modern classical tale on The Fisherman Of Ephesus that will keep you cogitating.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

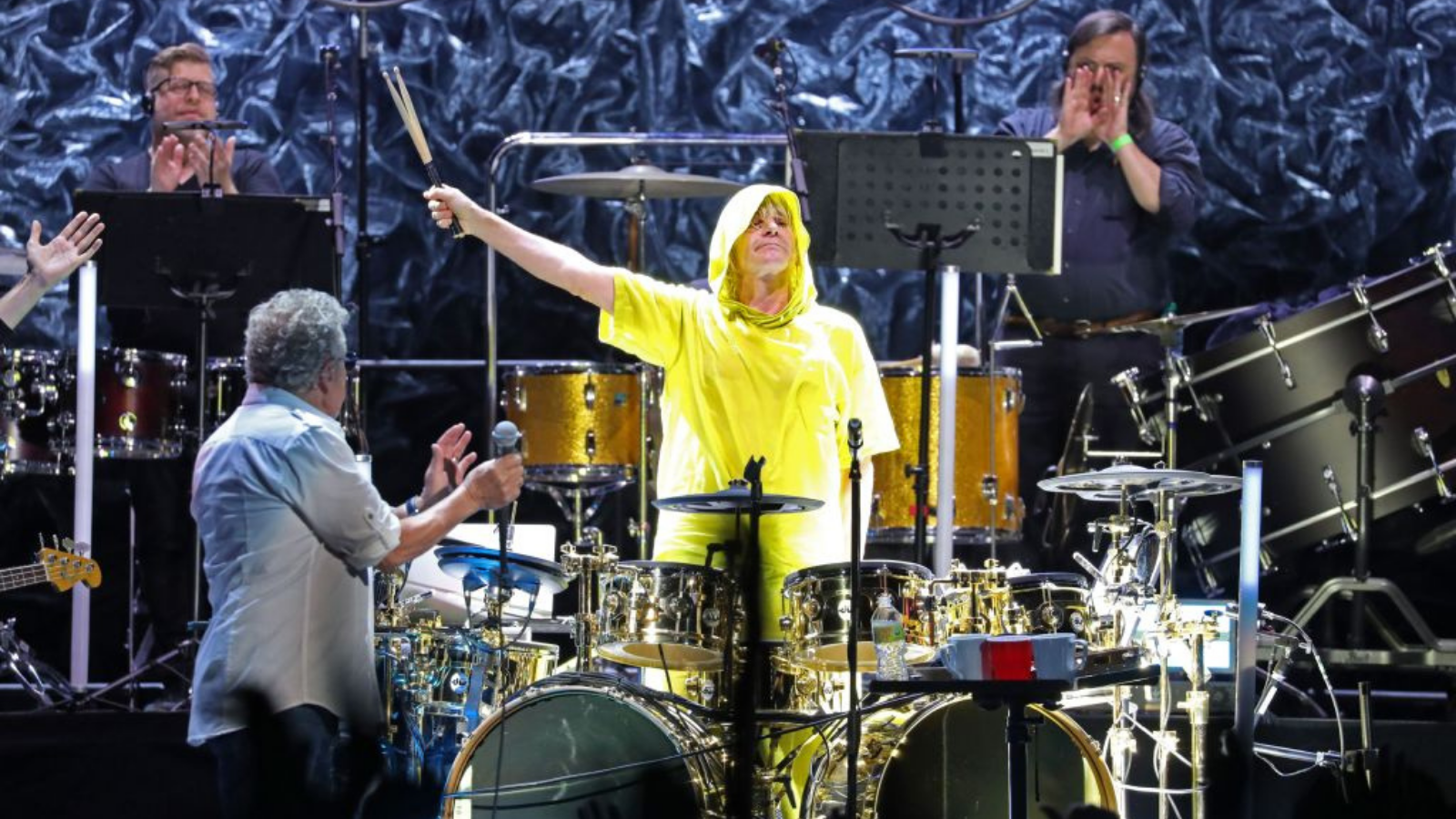

The music is light, bright, tight and recognisably Tull, with plenty of room for his flute to fly. But there are times when you yearn for a heavy guitar riff from the long-departed Martin Barre to add some heavy rock dynamics. It could also serve to distract from Anderson’s increasingly frail voice.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.