It’s perhaps odd that for many years Vangelis wasn’t perceived as cool whereas those innovators of electronica who’d come from the krautrock side of things were. The Greek composer, as emphasised in last month’s Prog interview, has a naturally reclusive nature and has rarely made the obvious career move, so in theory he carries faultless cult-hero credentials. Of course in plain terms he’s been too consistently successful to ever be rediscovered as a hidden treasure, but it does now seem as if time and tide have relaxed, allowing him to ascend to the status of revered sonic architect. His five decades in music have embraced and enhanced prog, jazz, classical, film scores and ambient as well as the electronic field, which he bestrides like a Colossus. Many are those who find within his creations something akin to a transcendent religious experience. He’s even had a star named after him.

For all his diversity, Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou, now 73, is probably still best known for movie scores like Blade Runner and Chariots Of Fire, where his unorthodox approach won love and converts through eventual familiarity. Some at the time dismissed them as pretty, inoffensive, aural wallpaper, but slightly sinister, incongruous undercurrents gave them an intangible aura of mystery. The young Vangelis had of course founded Aphrodite’s Child and come close to joining Yes, so challenging musical conventions and expanding the perimeters was in his blood.

Yes, there are long passages within his catalogue which putter along unremarkably – you wouldn’t be startled to hear them in an elevator – and he can seem content at times to hover in the flotation tank with gentle, unthreatening, electronic shimmers and throbs. Yet even there the accumulative Zen slow-burn has airy grace, and if it is elevator music, you’re kept wondering as to what you’ll see when those lift doors next open.

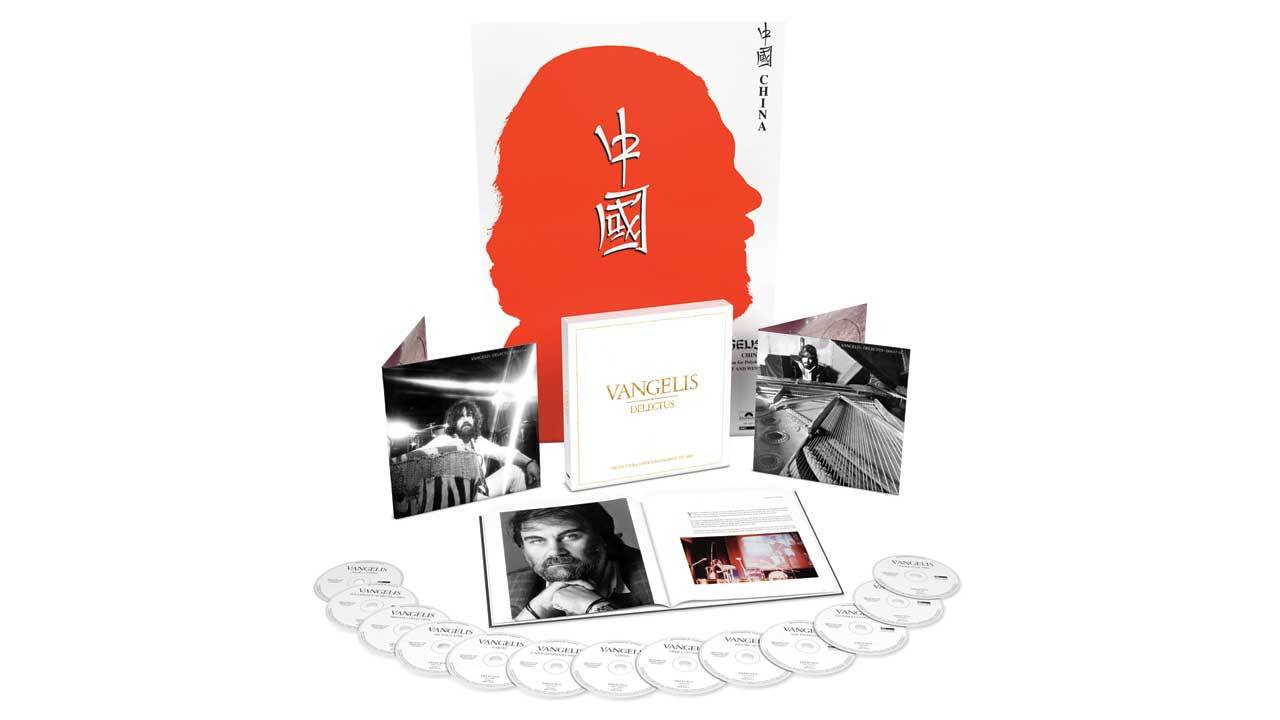

Appearing before us now is a 13-disc box set, cherry-picked from his work in the 70s and 80s and including all his albums for Vertigo and Polydor, remastered for the first time under the man’s own supervision. He’s expressed delight at being able to bring the sounds “to today’s standards”. This baker’s dozen, then, offers a sprawling range, from 1973’s Earth through to 1985’s Invisible Connections, as well as the three early 80s Jon & Vangelis collaborations. To be clear: there’s no Blade Runner, no Heaven And Hell, no Alexander. Pretty much everything else that built his legend is here though.

Earth, while technically his third, was his first solo album proper. As the title hints, it doesn’t shoot for the epic quite like Heaven And Hell was to, but it sees him transitioning from rock to mysticism – “we become a diaspora”, says the narrator – and confidently shunting the synths front and centre. Wildlife-doc soundtrack L’Apocalypse Des Animaux – recorded when Vangelis was still in Aphrodite’s Child, three years prior to its release – suggests a duality between melody and cosmic trance. We then skip to 1979 and China, where he dived into Eastern sounds and instruments despite never having been to that country, and earned a silver disc. 1980’s See You Later is atypically dystopian and vocal-heavy, while four years later Soil Festivities, a concept album about nature, sets the tone for a loose trilogy incorporating the African-influenced Mask and the ominous, treated eeriness of Invisible Connections. Opera Sauvage, scoring the 1979 French nature doc, emphasised his predilections regarding the planet. As did 1983’s Antarctica, the synthesisers proving adept at evoking cold and isolation.

The crossover which brought him in from that cold is ’81’s Chariots Of Fire, which made Vangelis an unlikely household name. The score won an Oscar, went to Number One in the States, and with its titles theme – cue slo-mo running while gulping for air – even delivered a US chart-topping single. We take its understated beauty for granted now, but imagine how radical a decision it was to use something so futuristic for a mainstream period movie (the first example of its kind). In typical artist mode, Vangelis has since spoken less than fondly of it. But as this reviewer, who lit up the screen for a good few milliseconds as a teenage extra in the film, can vouch: once that gliding refrain gets in your head, it’s reluctant to leave. It’d be too rich to suggest those pristine synths begat the 80s, but they sure contributed.

Vangelis was by then enjoying a fruitful musical rapport with Jon Anderson, even if he didn’t enjoy having to do things like appearances on Top Of The Pops. Anderson’s (first) departure from Yes freed him up to set words to his friend’s music (he’d appeared on previous Vangelis albums), and between 1980 and ’83 they released Short Stories, The Friends Of Mr. Cairo and Private Collection. The pair’s debut was patchy but the second was far superior, conjuring up the funky (!) title track which Quincy Jones “borrowed” for Thriller as well as the enchanting State Of Independence (a Donna Summer hit-to-be) and the duo’s own rather weedier hit I’ll Find My Way Home. Private Collection feels mediocre until you reach the 22-minute “side two” astral sojourn that is Horizon – and that’s Vangelis in excelsis. For Vangelis’ most ardent devotees – Vangelisciples? – this is the Holy Grail.

The man’s been a quiet groundbreaker, his influence gradual as opposed to pulling up trees, but this lavish collection (including a book, essay and rare photographs) elucidates his music’s enigmatic allure.