“It’s a true representation of Stone Temple Pilots’ music and also of Guns N’ Roses’ music when they were at their best – vicious, streamlined, living off strippers.”

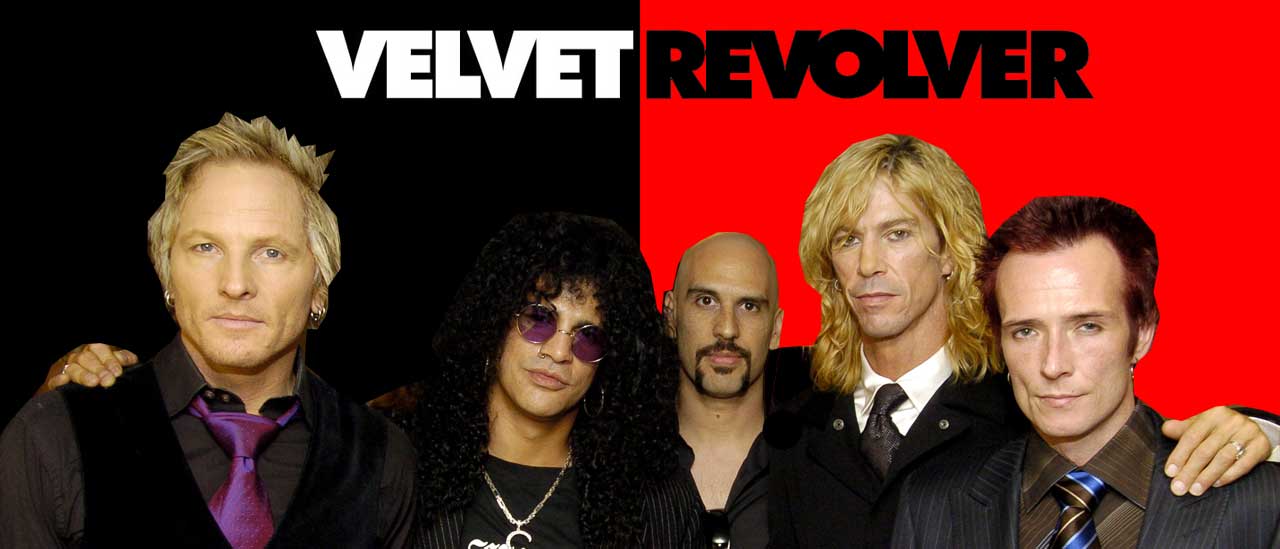

With that tantalising promise, Velvet Revolver vocalist Scott Weiland launched that band’s debut record to the press. It was a remark that had a certain swaggering arrogance to it. After all, Velvet Revolver contains just two (Slash and Duff McKagan) from the Guns N’ Roses line-up that recorded Appetite For Destruction, the only record they made while “living off strippers”, alongside Weiland himself from Stone Temple Pilots. So it would seem far from certain that these components contain enough of the essence of either band to ensure such a significant blend of the two.

The spin-offs and side projects of former members of GN’R have served merely to prove that no individual held the key to the Gunners’ creative fire; theirs was simply the happy convergence of talent, timing and opportunity.

Stone Temple Pilots were more dependant on the singular ability of Scott Weiland, and would have been faceless, as well as voiceless, without him. But they were a band who began their career to widespread approbation. They tagged on to the end of the grunge years, making the albums that everyone wished Pearl Jam would make after Ten – big, echoing, stadium-sized rock things lent nuance by Weiland’s nihilism.

Stone Temple Pilots seemed to get better, and more interesting, with every record. Their last, Shangri-La Dee Dah, was undeservedly overlooked, and Weiland appeared to become weirder, and more interesting, by the day. The straight-ahead, testosterone-led rock’n’roll so beloved of Slash and McKagan did not appear to be the most natural direction for a man prone to wearing a dress and indulging his fantasies of becoming David Bowie.

So Velvet Revolver possessed as much potential to become a curate’s egg as it did to relaunch the flagging careers of its members. That Contraband is as good as it is – and it is good, rather than great – is a triumph of faith over circumstance. Even as the band – completed by GN’R’s second drummer Matt Sorum, and Slash’s chum Dave Kushner on the other guitar – came together with some purpose last summer, Weiland was up to his old tricks and headed back for rehab.

“All things considered,” Slash said of his singer, “if you’d given me a handful of résumés I’d avoid the ones that said ‘irretrievable junkie’ on them, but in reality Scott’s dealing with stuff. He’s such an amazing talent.”

Enough of a talent, apparently, for Slash, McKagan and Sorum to accept the real possibility that they’d hooked themselves up with another gifted flake. While Weiland appears to lack Axl Rose’s megalomania, he shares the GN’R man’s propensity toward unpredictability. But when the tapes started to roll, the quality of the music, and the strength of the muse, overrode those concerns.

Sucker Train Blues, Doing It For The Kids, Big Machine and Illegal Song, the first four tracks on Contraband, lack the light and shade to convince that the correct decision had been made. They’re hard, driven songs, aggressive and fast, but they lack the sheer hip-swinging cool of Guns N’ Roses at their best. The missing ingredient is the one provided in GN’R by Izzy Stradlin’, the most underrated Gunner and the source of the cool rhythms that loosened up songs like It’s So Easy and Rocket Queen.

Velvet Revolver plunge forward boldly but to lesser effect. Weiland’s delivery is interesting, too. He cops some Rose-isms, for sure – but then hasn’t everybody? – yet his work is generally of a darker hue. His attempts at beat-poet mysticism are sometimes unintentionally funny (‘Somebody raped my tapeworm abortion/Come on, motherfuckers, and deliver the cow’ he sings during Sucker Train Blues), but he is quirky enough to keep some unchallenging songs afloat.

Fortunately for Velvet Revolver, things do get better, and the second half of Contraband is far stronger and leads one to conclude that part of what weakens the record is its track order. Having begun as an energetic, well-meaning thudder, it at last begins to repay the faith of those involved.

Fall To Pieces is a big, roomy ballad of the sort Weiland performs so well (STP’s Interstate Love Song and Plush come to mind), while You Got No Right and the concluding Loving The Alien (Sometimes) are stylistically similar but also loaded with good ideas and powerful sonics. On Superhuman Velvet Revolver capture that elusive blend of their source bands, too; it’s charged, druggy anthem would not be out of place on any of GN’R or STP’s best records.

Contraband avoids the curse of so-called ‘supergroup’ records in that it is not indulgent. There is a palpable desire to deliver on their promise, and a feeling of edge that can’t be faked. In that light, the band can be forgiven for talking themselves up so much.

It must be intoxicating to feel once more the drive and energy that founded their reputations all those years ago. Now they must surrender themselves again to the industry machinations that they dislike so much and yet have profited so greatly from.

This review originally appeared in Classic Rock 67, in May 2004.