Wembley Arena is on Tokyo lockdown. It’s three hours before the most important European gig of X Japan’s career, and every cranny of the venue attests to just how big in Japan they are. Nineteen cameramen, many on the band’s staff for years, point from the stalls, faithfully recording even the smallest move the group make. The narrow corridors backstage are choked with the entourages of the five band members, whose separate dressing rooms have impassable Japanese sentries.

As We Are X (a new film from the producers of Searching For Sugar Man) explains, X Japan are Japanese rock. They battered down the doors of their nation’s mainstream with visual kei, an extravagant, androgynous, highly localised hybrid of metal and glam. But the saga that has gripped their fans since they formed in 1982 also includes two band members committing suicide, and their singer, Toshi, being brainwashed by a rock-loathing cult.

The driving force behind their survival, and this first European arena show, is drummer, pianist and songwriter Yoshiki. He was so asthmatic and sickly as a child that his mum didn’t expect him to live. We Are X shows him enduring multiple injections to combat chronic injuries, including a neck bone deformed by decades of headbanging, a torn ligament, tendonitis and carpal tunnel syndrome, leaving one drumming wrist in a splint. “I should not be playing,” he confesses casually.

An oxygen tank and mask are routinely kept side-stage for when he collapses.

Yet here Yoshiki is, in a dramatic soundcheck that’s also a tune-up for his lithely athletic-looking but internally fucked body. He begins on his own-brand, glass-topped piano, then he drums, for 30 bruising minutes. The bass drum sounds like the heavy rumble at the start of the Flash Gordon theme, and there’s sonic chaos as he works round his kit to a symphonic backing track. The lights pin him, glittering silver-white like a cyborg. Then he drums with just his busted wrist. Eventually he stands stock-still on his drum stall, pinned in a heroic pose by white lasers. “That’s it, thank you,” he states.

Only then are the thousands outside let in for a pre-gig screening of We Are X.

Four days earlier, the film premieres at a Soho cinema. It takes testimony from fans including Gene Simmons and Marilyn Manson, and sketches the band’s evolution from punky speed-metal teenagers to the glam-metal showmen who’ve sold a reported 30 million albums. What makes their latter-day penchant for giant power ballads so affecting, though, is the genuine trauma behind them. When Yoshiki was 10 years old, his dad committed suicide, leaving him with his own death wish. Then singer Toshi’s brainwashing by a sinister cult fractured the band at its peak, leading to a bad‑tempered farewell gig at Tokyo Dome in 1997. Five months later, lead guitarist Hide committed suicide, and several grieving fans followed suit.

With Toshi soon to quit his cult, X Japan reformed in 2007. Then in 2011, their original, wild bassist Taiji, who’d been sacked in 1992, killed himself too.

“The pain made me compose all these songs,” Yoshiki unsurprisingly says, when he appears for a Q&A after the premiere. A Hong Kong super-fan pipes up here about an absence in the film that clearly troubles him. “Are there any ladies – in your past, or present, or,” he concludes with an edge of desperation, “your future?”

Yoshiki dodges the question at length. In fact, like his British glam-rock heroes, Bowie especially, he’s an asexual, feline presence, gently spoken and unthreatening. This may explain the huge preponderance of female X Japan fans, who fill several rows of the cinema. Like Bowie, Yoshiki is a throwback to the days when rock stars were pop stars too.

When I meet him in his Kensington hotel a few hours earlier, he’s dressed in black leather, from his rocker’s boots up. That dodgy wrist is still in a splint. “We’re looking into stem cell research,” he says, vaguely.

Given such severe physical limitations since childhood, are his onstage exertions a way of proving something to himself? Saving himself, even?

“You can say that, yeah,” he replies. “Trying to go beyond my limits. Because I had asthma and everything growing up, and I was always going to hospital, I was so limited. People told me, ‘You can’t run, you can’t do this, you’re weak.’ So now I feel like nothing’s impossible, and I’m always telling myself that. I just want every show to be something meaningful.

“Even when I almost get to the point of fainting, I feel very good, for some reason!” he laughs. “I’m almost killing myself every show, then resurrecting somehow. I still have a death wish. But the death wish I had before was negative – trying to escape from life. And now it’s very different. I’m trying to live each moment as much as I can.”

The film provides a ready-made mythology, with all the roller‑coaster extremes and tragic fatalities of classic rock bands of yore – a good way to lure new, non-Asian fans in.

“Possibly,” Yoshiki says. “But we are not trying to make a promotional film. We’re trying to make something meaningful. My agent asked us to do a documentary several years ago, and I said no. Then people started saying, ‘Your life story can save people’s lives. This film can give people the courage to move on, who have depression, who have been suffering some kind of internal pain.’”

Rock certainly saved Yoshiki, back in 1975. Kiss’s Love Gun was the first album he bought, while he and childhood friend Toshi soaked up Queen and Bowie albums too. They were 10 years old, in a year when Yoshiki needed something to cling to.

“Till my father took his own life, I was playing and listening only to classical music,” he says very softly. “But when I lost my father, I was lost. Didn’t know what to do. Just screaming and breaking things, and then I found out about rock, where you can do those things – legitimately! I needed rock.”

Japan, it turned out, also needed X (their moniker till 1992, altered because of LA punk band X).

“Japan was very conservative thirty years ago,” Yoshiki recalls. “You didn’t see anyone with dyed hair. I think we shocked Japan. We created the visual kei movement, which is not only being flamboyant and wearing a flashy outfit – it’s more a freedom of how you can describe yourself. You can be who you are. You don’t have to care about what people say. That kind of spirit.

“Early on we were a punk-rock band,” he adds, “and I used to have spiked hair all over. Then one day I only had time to spike one side, and people liked it. And we were playing very heavy music, and some critics came and said to us, ‘If you’re playing heavy music, why don’t you play in a more masculine outfit?’ I was like, great! So the next week we turned up as feminine princesses.

“We did everything we were told not to do,” he says wryly. “We were rebels.”

Now that attitude’s led them to Wembley Arena. Wouldn’t they prefer the far bigger Stadium?

“Yeah – someday, before I die!” Yoshiki replies, laughing. “I think it’s possible. It’s not easy. In 2011, we played Shepherd’s Bush Empire, and now Wembley. Maybe we’ll have to have the O2 in between…”

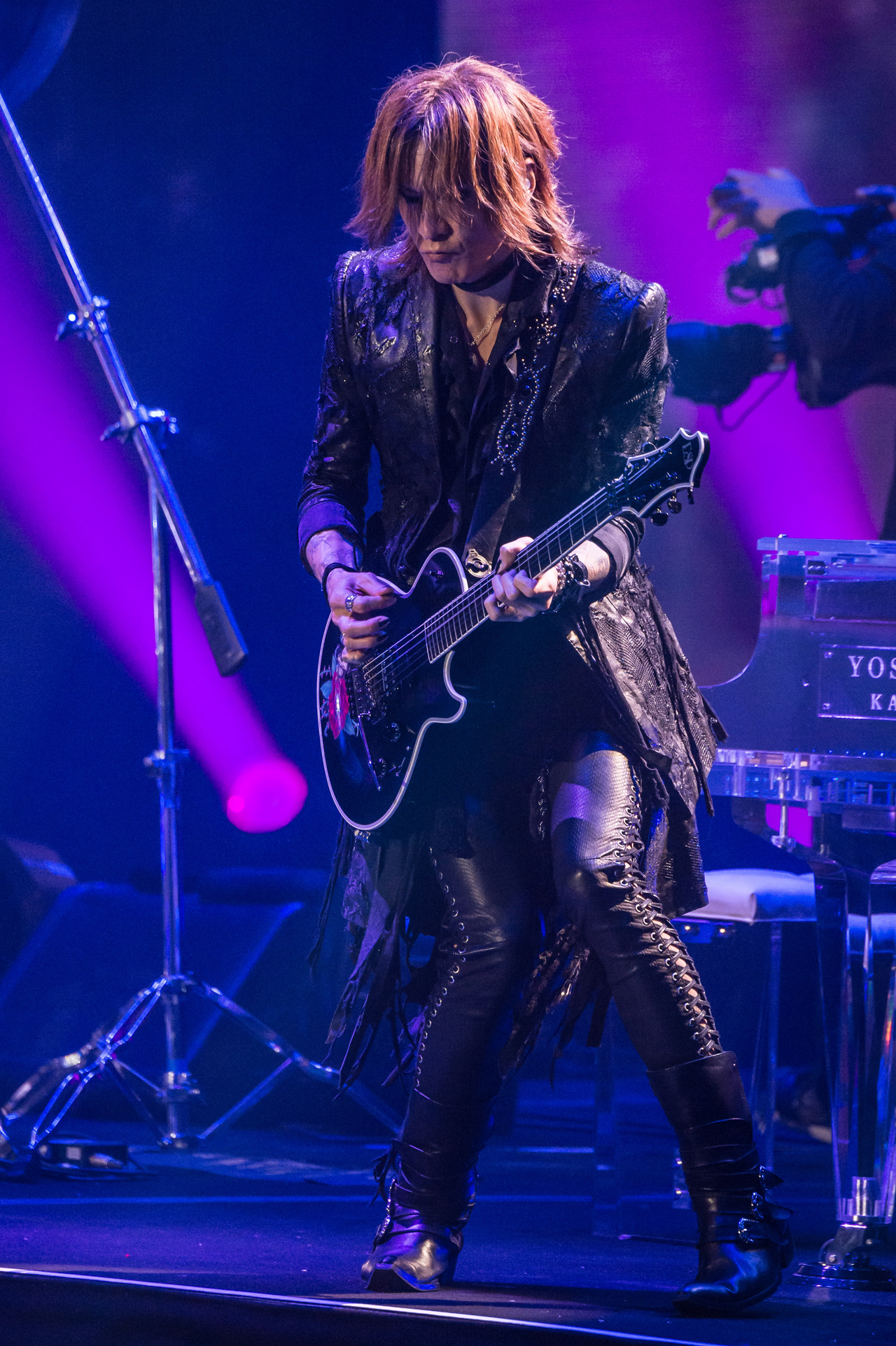

At Wembley, as showtime approaches, visual kei has taken over the make-up room. Hide’s replacement, Sugizo, sits speed-riffing and feedbacking on his guitar as two hairdressers sculpt his wind-blown locks. Heath, bassist since Taiji’s sacking, is next in the barber’s chair. With his flouncy Byronic shirt and piratical, red-tassled hair, he looks like a cross between Chrissie Hynde and Keith Richards.

Front of house, the healthily full audience are quietly watching We Are X. Standing backstage, there’s a weird, muffled echo to the film’s voices, with its screen visible in a slit above the dark stage.

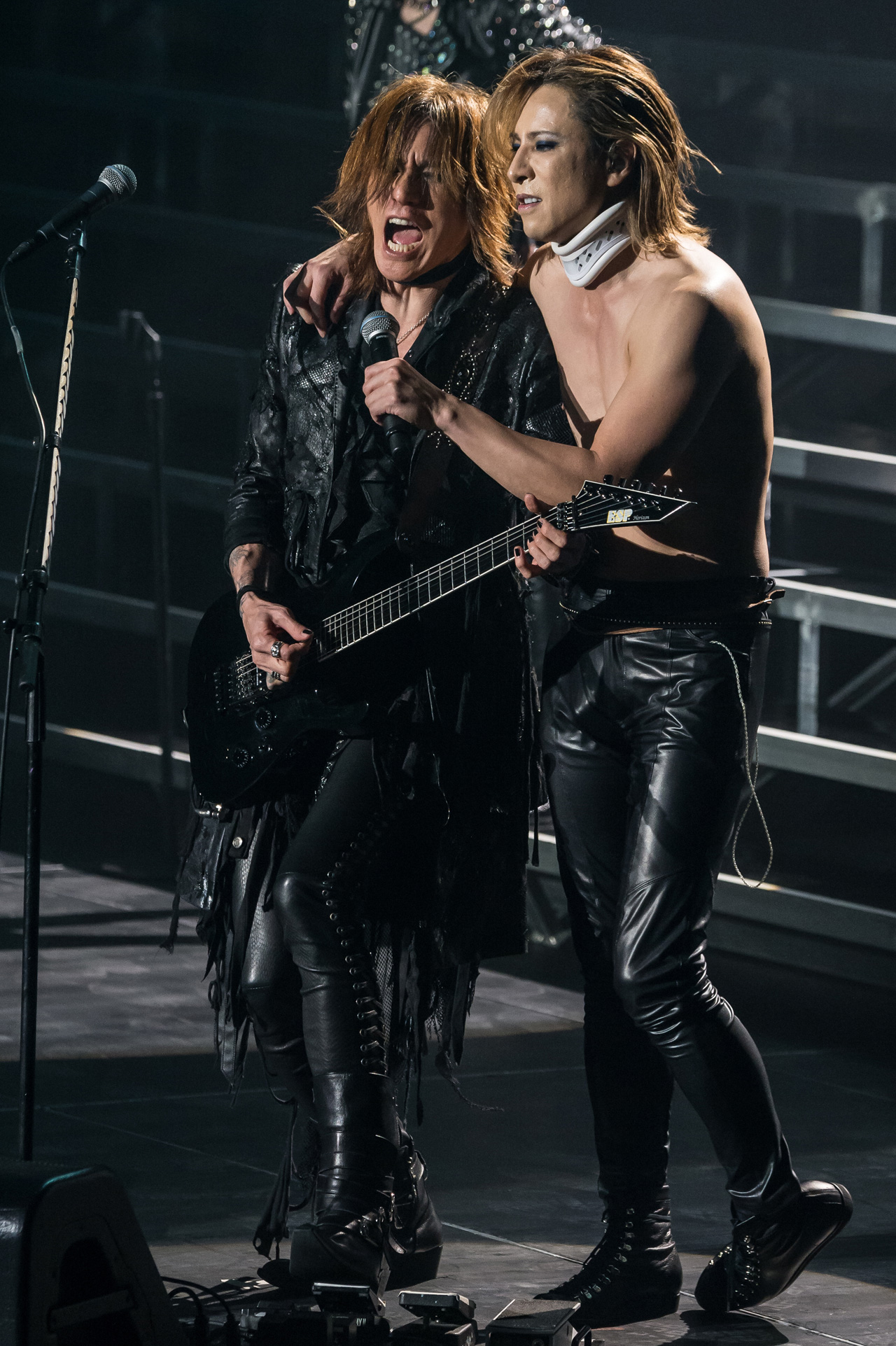

In a concrete antechamber, singer Toshi, a boxy figure in shades and 80s studded leather, is still having his hair tonged and teased. On the cinema screen, a giant, bare-backed Yoshiki prepares for Madison Square Garden, while the real thing steps up to Wembley’s drum riser in the dark. I’m right behind him, and there’s a stomach lurch of expectation as he signals for the curtain to rise.

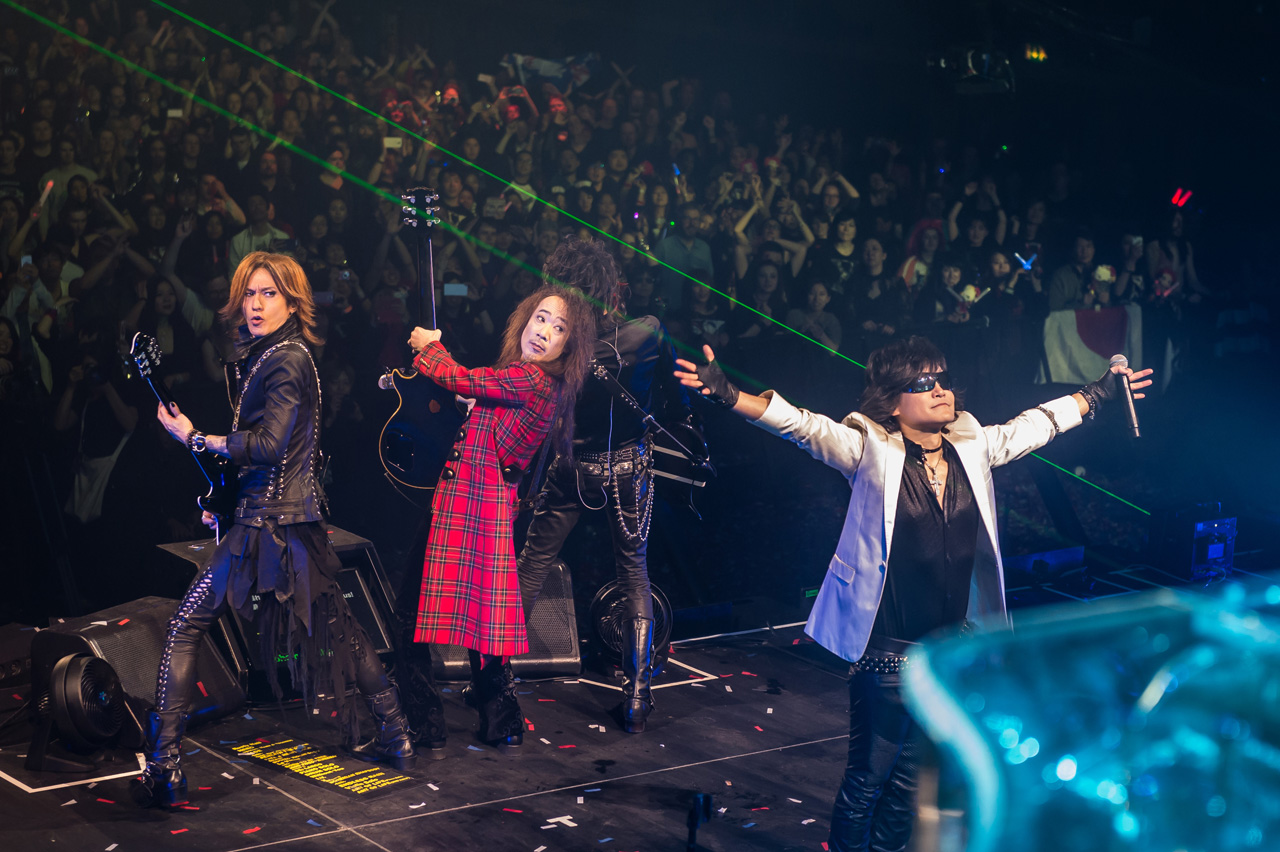

Toshi rouses the crowd with the band’s unifying call-and-response – “We are… X!” Then Yoshiki smashes a drum, there’s an ear-popping explosion of pyrotechnics, and they’re on.

His neck brace a sop to physical sanity, Yoshiki’s focused energy lifts him off his seat as he smacks a cymbal. Jets of flame heat the air behind him as Kiss The Sky lets Toshi at a ballad. His voice isn’t the biggest, but it’s all yearning uplift.

The size of the crowd isn’t just a hollow expats’ victory – there’s a very large, non-Japanese minority. One long-haired Anglo, hoarse and cackling, has a blast leading chants of “We are… X!”, while at the front, fans sport red hairdo homages to the band’s old, spiked look. It’s coming out day in the UK for this rock tribe.

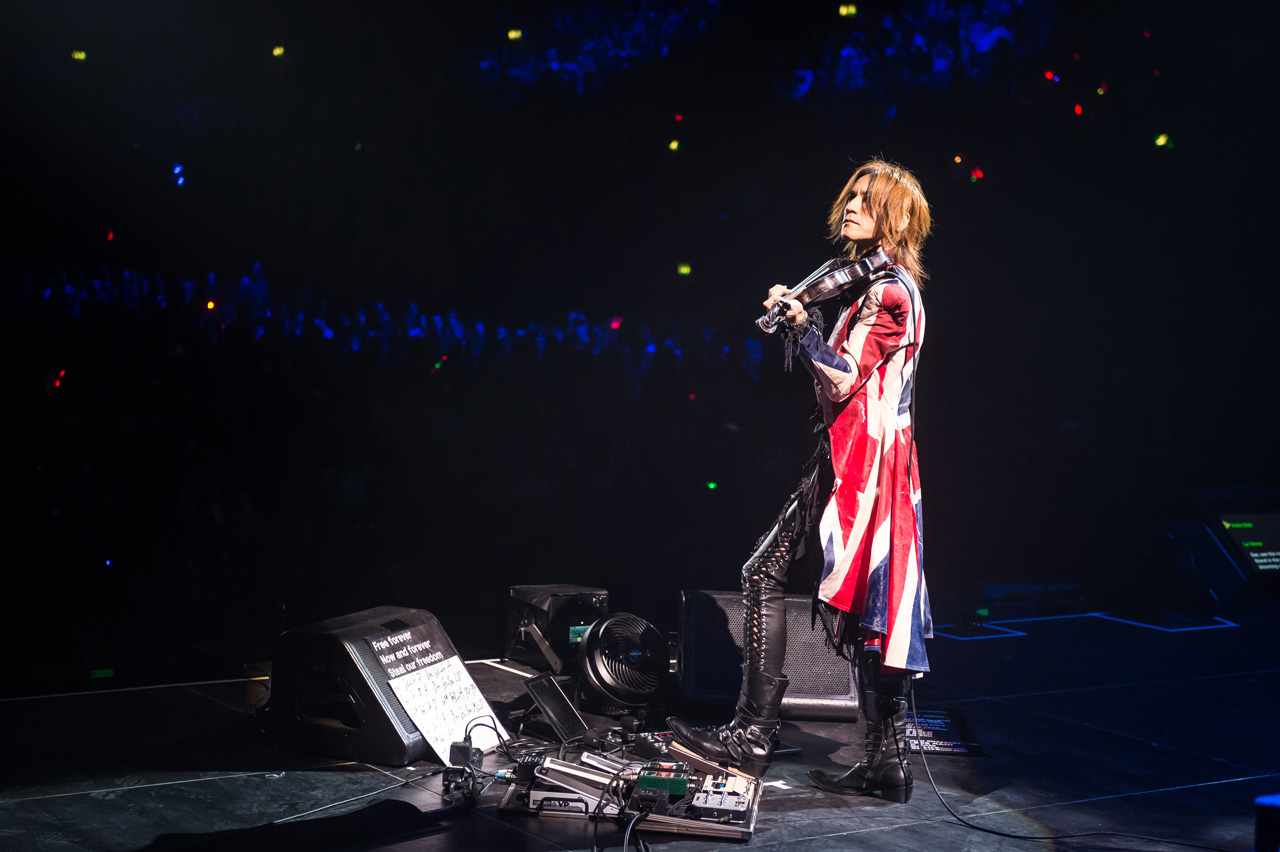

When Sugizo takes to the stage alone, he’s wearing a Union Jack frock coat, just like the one Bowie wore for Earthling. As cosmic dust swirls on the big screen, his violin solo slashes and cries movingly through Life On Mars, played to a symphonic backing track.

Then rose petals tumble to the floor and Toshi takes centre stage for La Venus, with its typically huge, death-haunted, Yoshiki-written sentiment: ‘Till we fly from here to heaven…’ As he croons the last note till it cracks, and sparkler pyrotechnics erupt, a woman near the front wipes her eyes.

There’s cordite in the air for the biggest explosion yet, which comes at the end of the headbanging Born To Be Free. And soon after the last notes fade, the band are off.

Backstage, you can hardly hear the crowd’s chants. For five minutes, then ten, Yoshiki’s courtiers wait outside his dressing room. There’s a piano in there, and he sounds quite lost in a classical tune. Axl Rose’s minders would be getting twitchy now. When he does suddenly sweep out in a long, white coat, 10 people form a column around him. Visual kei’s emperor mustn’t be alone.

The encore that follows earns Yoshiki all the backstage recitals he wants. After a piano solo that ends in a smashing cacophony, he stands on his drum stool, stock-still, just as he did at the soundcheck. He starts to play jazzy fills, then attacks the drums until the beats seem to splinter like shards of glass, and white light illuminates him.

He stands again, looking very tired, then takes a second, full-on drum solo. Toshi takes over to sing their tribute to Hide, Without You. Then Yoshiki pours a bottle of water over himself and, dripping, growls over and over, leading the crowd like it’s the most meaningful, joyous thing in the world: “We are…” He hits a giant gong then boots it down the stairs. Finally he lies prostrate on the piano, gasping: “We are…”

The encore alone has been a thrilling, relentless statement.

And then, after three hours, with the crew waiting impatiently to dismantle the stage, Yoshiki’s back again. He plays Bohemian Rhapsody on the piano, then a sad and glorious Space Oddity. He talks at length, about the acts who’ve played this place who meant so much to him and Toshi as kids, his voice breaking when he remembers his dad’s death, and again at “our days rocking clubs… actually our best memories”, back when all of the band’s members still were still alive.

His emotions stay near the surface while he speaks, his old wounds almost visible to the audience. “Without you guys,” he says to the crowd, “I don’t know even if I’d be alive.”

It’s not hokey when it’s true.

Near the end of a set reaching Springsteen proportions, Yoshiki’s still steaming on the drums, till he falls to the floor. Neck brace ripped off, his chest is pumping, his eyes closed, and he’s smiling. Though this usually happens, it’s more than James Brown ritual. He needs his half-dead rest.

There’s a long, lingering goodbye, ending with Yoshiki’s final, dervish-spinning, emotion-swollen, “We are… X!” Why leave vocal chords out of his body’s demolition derby?

Afterwards, he has time for one more word with Classic Rock, and we have to ask him if playing Wembley meant all that he thought it would.

“Yes. Even though we’ve played much bigger venues in Japan, we were influenced by a lot of UK artists, so it was a really big moment for us. We are moving forward, slowly but surely.”

And how, really, did Yoshiki keep going to the well so often, with a body that shouldn’t even have been up on the stage at all?

“I get amazing energy from the audience,” he replies. “Also, I try to play like there’s no tomorrow. Every single drum hit, it’s like it’s the last hit of my life.”

We saw X Japan live three nights in a row and went mad