As Tolstoy put it in War And Peace: “Because of the self-confidence with which he had spoken, no one could tell whether what he had said was very clever or very stupid.”

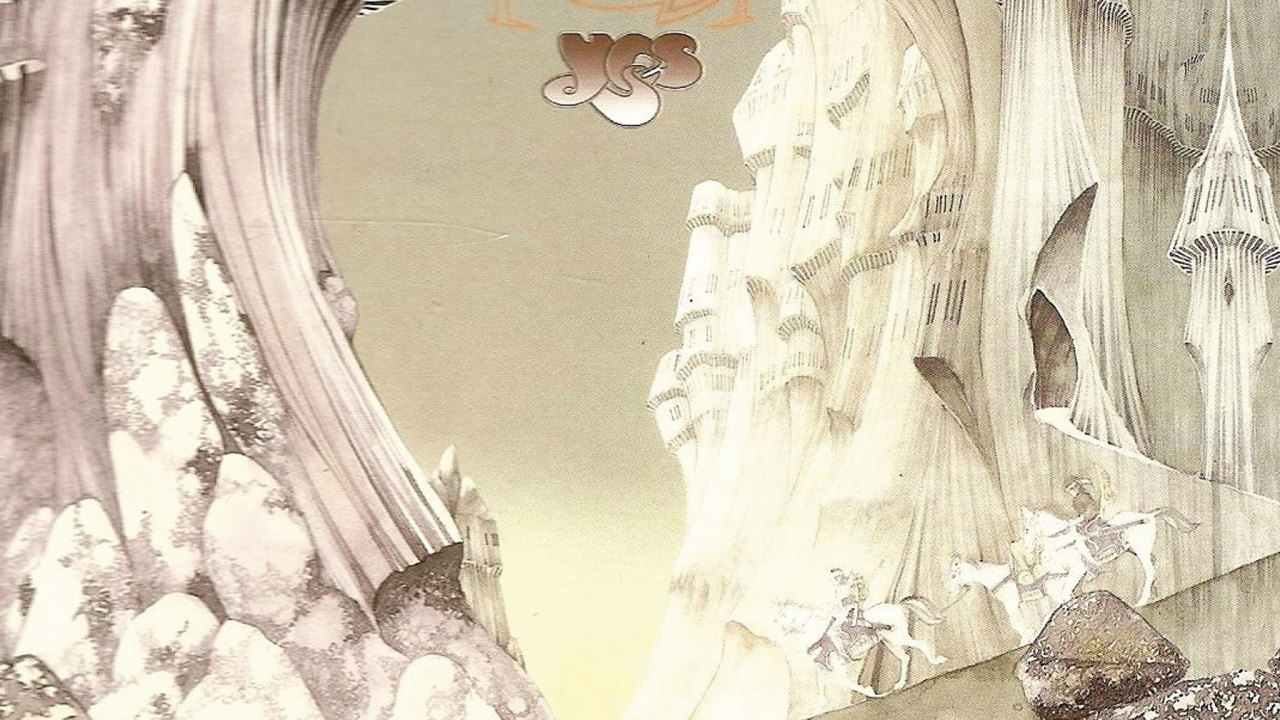

Yes’s 1974 follow-up to the divisive Tales From Topographic Oceans, inspired in part by that book, bewildered people almost as much as its epic predecessor.

On one level, it was a retreat from the precipice. Forty minutes long, with one full-side track and two sharing the flip, it resembled Close To The Edge; a tacit acknowledgement that Tales had drifted too far, maybe. Yet it also explored entirely new terrain, offering more aggressive, experimental sounds on the gigantic The Gates Of Delirium. Some of us are used to tutting and head-shaking when we declare this the greatest Yes creation of all, their very pinnacle. But as years pass we are growing in number, and with this Steven Wilson surround-sound mix, our case is formidably strengthened.

With Rick Wakeman leaving, disillusioned by his distaste for Tales, Patrick Moraz – ex-The Nice spin-off Refugee – arrived on keyboards, after Vangelis didn’t fancy the tour commitments. The odds were against him carrying off Wakeman’s cape, but on his only Yes album (recorded at Chris Squire’s home studio) he plays a blinder, like a super-sub scoring a hat-trick. Fearlessly, he both shows off and fits in, bringing fresh jazz colours to the band’s palette.

Anderson’s ideas for Gates, berating the timeless lust for war, were translated by the band into a floating, then furious, bliss-becomes-barrage of sound. The battle sequence sees thrilling input from Steve Howe (switching from Gibsons to Telecasters), Squire and Alan White (bashing bits of metal with Anderson). The solos are lacerating; the net effect somehow takes their ice and makes fire.

Anderson, meanwhile, gives the best vocal of his career, the sublime epiphany of the coda (‘Soon, oh soon the light’) one of the most beautiful resolutions in 70s music. Sound Chaser and To Be Over are likewise brimming with wonder.

Latterly, the personnel responsible have muttered that perhaps it was too busy, and that an excess of punchy ideas were compressed into (ironically for Yes) too short a time. Well, part of its magic is that you can’t see the joins: you marvel at how this glorious collage of noises was possible. And now Wilson has, as is his forte, cleaned and clarified without diluting the mystique.

All these years on, Relayer sounds more boldly improbable than ever, the finest encapsulation of their unique genius.